Pre-Breeding Work With Grasspea and Finger Millet Gets a Boost

Grasspea at ICARDA’s facilities at Marchouch Station, Morocco. Photo: Michael Major/Crop Trust

Grasspea at ICARDA’s facilities at Marchouch Station, Morocco. Photo: Michael Major/Crop Trust2 October 2019

Two food crops prized for their nutritional value and ability to survive temperature extremes, drought and poor soil are now receiving the attention they deserve. A new project led by the Crop Trust will help improve the productivity of grasspea and finger millet by making more genetic diversity available to breeders.

Plant breeders need genetic diversity in order to improve the yield and nutritional quality of crops and adapt them to changing climatic conditions. But that diversity is limited in cultivated grasspea and finger millet. However, in recent years, pre-breeders working on the Crop Trust’s Crop Wild Relatives Project have expanded that diversity by tapping into wild and ancient domesticated forms of the two crops.

This new project, funded by the Templeton World Charity Foundation, Inc., will allow pre-breeders to continue their work and ultimately contribute to food security, human health, income for rural poor, while protecting the environment.

Jamal Mabrouki, an ICARDA technician, crossing grasspeas at ICARDA’s facilities at Marchouch Station, Morocco. Photo: Michael Major/Crop Trust

Shiv Kumar Agrawal carrying out grasspea evaluation at ICARDA, Rabat, Morocco. Photo: Michael Major/Crop Trust

A grasspea project launch meeting was held at JIC in Norwich in September 2019 to bring together the teams from ICARDA, JIC and JHI. From left: Benjamin Kilian (Crop Trust), Shiv Kumar Agrawal (ICARDA), Paul Shaw (JHI), Saleha Bakht, Cathie Martin, Travor Wang, Noel Ellis, Anne Edwards, and Abhimanyu Sarkar (all JIC).

Ridding grasspea of toxins

“Grasspea is a nutritious crop which is heat- and drought-tolerant and often survives when other crops fail, thus gaining a reputation as a ‘famine crop’,” said Shiv Agrawal, a legume breeder with the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), who will spearhead the work on grasspea in the new project. The problem with the crop is that it contains a toxin that can cause paralysis if people eat too much of it as a sole food source.

“Our results to date in the Crop Wild Relatives Project grasspea pre-breeding work have been very promising. We have been able to identify wild species which have low toxin levels,” said Shiv. “And we have broken through a major technical hurdle by successfully crossing two species of grasspea.” This project will now allow the team to take the next step and breed toxin-free, climate-smart grasspea varieties.

Plant breeding can take a long time and it can be a “hit and miss” practice unless you have a way of knowing which genes you are transferring. Shiv will be able to fast-track the process by using the latest genomic tools. ICARDA will be working closely with the John Innes Centre (JIC) in the United Kingdom, who will be improving the reference genome for grasspea. By mapping the genome sequence of both cultivated grasspea and its closest wild relatives, Shiv’s team can accelerate the pace of breeding by “tagging” those genes in the wild species which he wishes to transfer to the cultivated crop.

Developing a Striga-resistant finger millet

Finger millet is also a highly nutritious, drought-tolerant crop, but one that still doesn’t get the research attention it deserves. “We have the potential to significantly increase yields in East Africa, where finger millet is an important subsistence crop for small-scale farmers, particularly women,” said Damaris Odeny, a molecular geneticist with the International Crops Research Institute for Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) in Nairobi, who led the Crop Wild Relatives Project finger millet pre-breeding work.

Finger millet yields are stagnating in part due to a sap-sucking plant parasite known as Striga and blast disease. Damaris’s national partners in Kenya have succeeded in developing crosses between wild relatives of finger millet and its cultivated varieties that show promise for Striga and blast resistance, as well as tolerance to drought. Several superior crosses have already been identified and crossed again with varieties preferred by farmers in the country. Some of these are currently undergoing adaptation trials and will subsequently be released in Kenya for use by farmers.

“The Templeton-Crop Trust project will now help us make this newly developed breeding material available to other countries in East Africa,” said Damaris. “Our objective is to develop successful and well-integrated pre-breeding programs in Ethiopia, Uganda and Tanzania, as well as Kenya, so that we can capitalize on the rich genetic diversity that exists in these centers of finger millet diversity.”

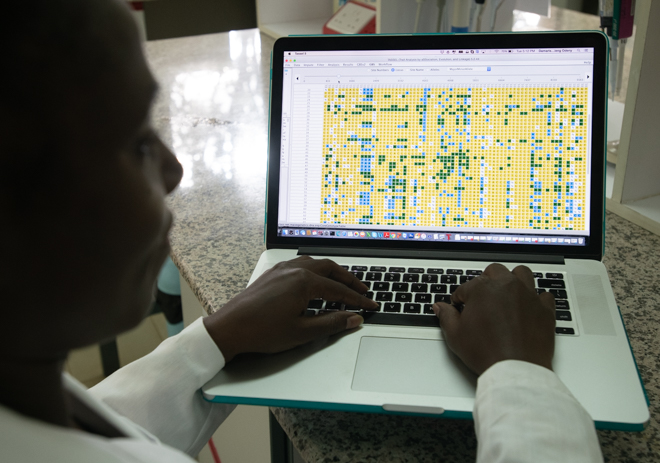

ICRISAT’s Dr. Damaris Odeny focuses on genotyping finger millet samples. Photo: Michael Major/Crop Trust

ICRISAT’s Damaris Odeny analyses SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphism) to detect differences in the DNA of different finger millet samples. The work to identify these SNPs will help guide finger millet breeders when selecting beneficial traits. Photo: Michael Major/Crop Trust

A project launch for members of the finger millet team was held in Nairobi in September 2019. From left: Gang Roggers (NaSARRI, Uganda); Dennis E. Tippe (TARI, Tanzania); John Adriko (BBP, NARO, Uganda); Esther Amayo (ICRISAT-Nairobi); Mathews Dida (Maseno University, Kenya); Damaris Achieng Odeny (ICRISAT-Nairobi), Amare Seyoum (EIAR, Ethiopia); Henry Ojulong (ICRISAT-Nairobi); Chrispus Oduori (KALRO-Kisii, Kenya), William Chrispo Hamisy (NPGRC, Tanzania); Victor Wasike (GeRRI, Kenya).

Finger millet can withstand cultivation at altitudes over 2000 m above sea level, has high drought tolerance, and high levels of micronutrients. Photo: Michael Major/Crop Trust

Templeton-Crop Trust project co-director Benjamin Kilian (right) with the Crop Wild Relatives project’s finger millet pre-breeding partner, Chrispus Oduori and Margaret Kubende, a farmer, in her finger millet field in Kakamega County in Western Kenya. Photo: Michael Major/Crop Trust

Sharing the data

Projects like this generate vast amounts of data – which needs to be shared with researchers and breeders worldwide if it’s to do any good. “We are excited that this project allows us to further build on the work carried out thus far for the CWR Project by the James Hutton Institute (JHI) in developing Germinate,” said Benjamin Kilian, a senior scientist at the Crop Trust and co-director of the Templeton-Crop Trust project.

Germinate is a database software, specifically tailored to handle the voluminous and complex data arising from pre-breeding and similar activities. “The data for both crops will be added to Germinate, and we will develop additional online tools so that breeders and other stakeholders globally can select the most promising material for their programs,” said Paul Shaw, a research leader in Information Systems at Hutton.

Crop Trust and Templeton: Common goals

“We’re extremely grateful to the Templeton Foundation for their foresight in supporting this important pre-breeding work,” said Marie Haga, Executive Director of the Crop Trust. “These two crops offer enormous potential to help ensure the food security of vulnerable smallholders at a time when the climate is changing. Yet, regrettably, funding for improving these crops has been limited. The Templeton Foundation is helping to break that bottleneck and we are excited that these most-deserving crops will now receive increased attention.”

###

All material generated by this project will be shared under the terms of the Standard Material Transfer Agreement (SMTA) within the framework of the multi-lateral system of the International Treaty for Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture.

More information

Finger millet (Eleusine coracana)

- Finger millet is a drought-tolerant cereal grown and consumed in the arid and semi-arid parts of Southern and Eastern Africa, where it originated, as well as parts of South and Southeast Asia.

- Can survive in soils with low levels of nutrients.

- Has a short growing season and requires few inputs.

- One of the most under-researched and under-funded cereal crops in the world.

- A source of protein, iron and fiber; the grain is gluten-free, contains a high concentration of unsaturated fatty acids and is exceptionally rich in calcium – up to 10 times more than most cereals – folic acid and amino acids.

- High levels of tannin mean the seed can be safely stored for extended periods.

- In Africa, it is predominantly grown by poor, smallholder famers, the majority of whom are women.

- In East Africa, average yields are around 1.3 tons per hectare, in comparison to its expected potential to produce over 10 t/ha.

Grasspea (Lathyrus sativus)

- Commonly grown as an “insurance crop”, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

- A heat- and drought-tolerant legume that often survives when other crops fail.

- Tolerates moderate salinity and waterlogging.

- Seeds are protein-rich and a good source of iron and zinc.

- A nutritious feed for cattle.

- No major threats from diseases and insect pests.

- Neglected due to the presence of the plant toxin β-N-oxalyl-L-α,β-diaminopropionic acid (ODAP). Continued excessive consumption can cause lathyrism in humans, a neurodegenerative disease that can result in paralysis of the lower limbs.

The three-year project, Safeguarding crop diversity for food security: Pre-breeding complemented with Innovative Finance began in August 2019. Project partners include:

- International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA)

- International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT, Nairobi)

- James Hutton Institute

- John Innes Centre

- Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organisation (KALRO)

- Ethiopian Institute for Agricultural Research (EIAR)

- National Agricultural Research Organisation (NARO) of the National Semi Arid Resources Research Institute (NaSARRI), Uganda

- Tanzania Agricultural Research Institute (TARI)

Categories: Templeton Pre-Breeding Project, Climate Change