Arroz e Feijão

15 August 2016

There seems to be a bit of an issue over at the Olympics with fast food marketing, but if athletes in Rio, or indeed spectators, want a simple, cheap meal that’s also healthy, and hopefully sourced more sustainably, they could do a lot worse than tucking into the Brazilian staple of rice and beans (but don’t forget the vegetables and the tropical fruit juice). This is such an established part of Brazilian life that EMBRAPA, the country’s agricultural research organization, has a whole research unit called Arroz e Feijão – Rice & Beans.

Unfortunately, the level of attention beans get in Brazil is not typical around the world, even in other places that eat a lot of them, and the situation is even worse for other pulses – the general term often used to refer to the dry seeds of members of the plant family Leguminosae (technically, it’s now called the Fabaceae, but life is too short as it is), crops like chickpeas, lentils, peanuts, cowpeas and a host of others. That, at least, is the contention of a paper just published in Nature Plants, which also sets out to show that this relative neglect has been bad for global food and nutritional security.

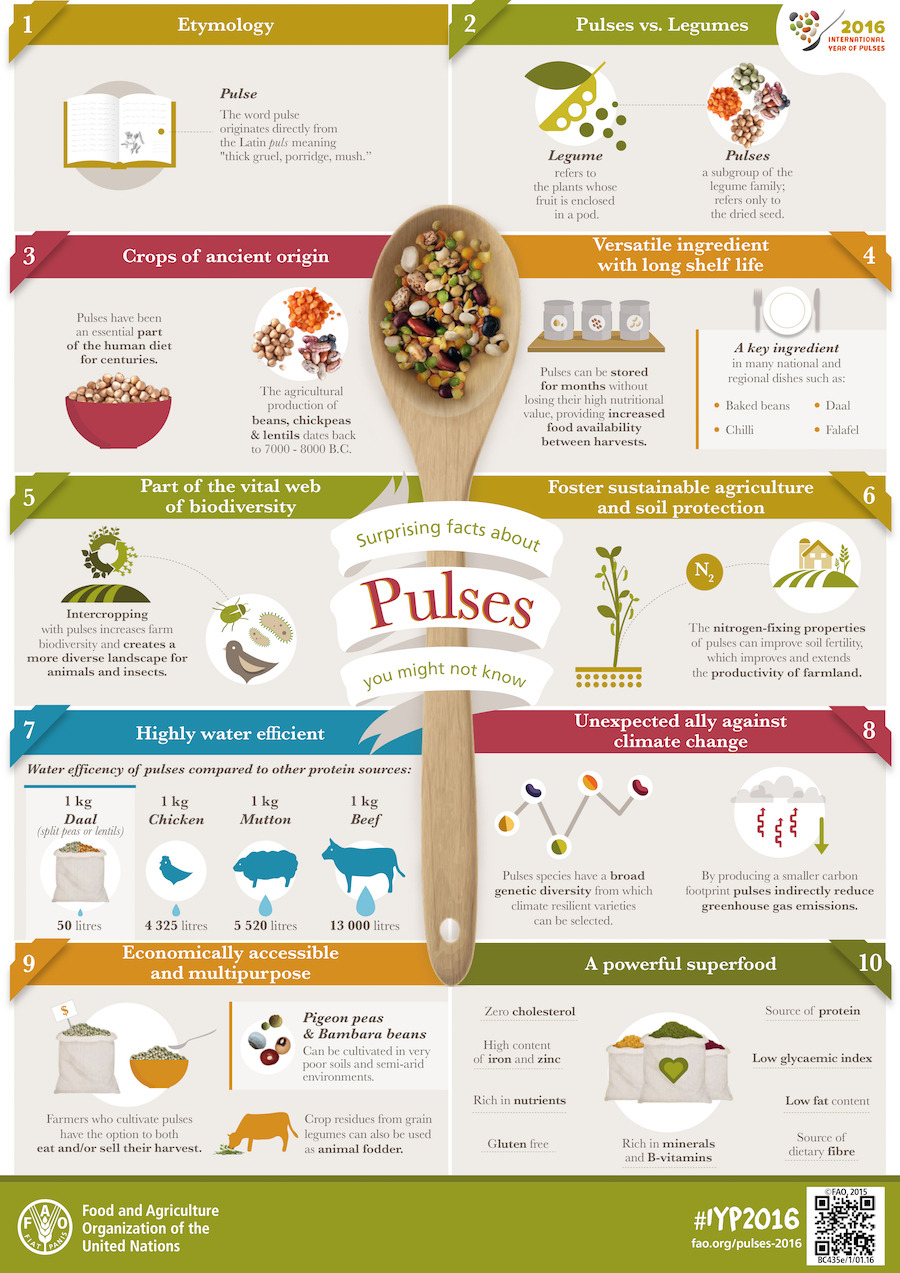

Now, this is not news. 2016 is, after all, the International Year of Pulses. The UN General Assembly doesn’t pick the subjects for international years out of a hat. It is widely recognized that pulses have not been getting the research investment their importance in agriculture and food systems deserves. But, as no politician ever said, it’s always good to have the data. And the Nature Plants review provides lots of data.

The data show, for example, that improvement in the yield of pulses has been lagging behind that of cereals (300% over the past 50 years vs 60%). That in too many cases increase in production has come from agricultural expansion. That globally we’re not making good enough use of that fabulous ability of leguminous plants to pluck nitrogen from the air and, in essence, make their own fertilizer. That eating pulses is really good for you, and for the environment. That we know way too little about some pretty promising species; but also that some great resources are now available to delve into their genomes, and more are on the way.

[© FAO] [2016] Surprising facts about pulses you might not know www.fao.org/resources/infographics/infographics-details/en/c/382088/

The paper also has a very useful table summarizing genebank holdings for 19 pulse crops. It’s worth quoting at length what the authors say about that:

It is therefore important to have a systematic inventory of legume germplasm centres and their collections. Most of the publicly available information can be found in GENESYS (Global Gateway to Genetic Resources). In addition to major CGIAR (Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research) institutes listed in Table 1, significant numbers of grain legume germplasm collections are conserved in various national genetic resource centres. Germplasm from China can be accessed via the Chinese Crop Germplasm Resources Information System and the Crop Germplasm Resources Platform under the Ministry of Science and Technology, China, with some restrictions. The National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences (NIAS) Genebank holds the largest germplasm database in Japan. The germplasm from India can be accessed through the National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources (NBPGR) database. This germplasm list is not exhaustive because information is often hard to retrieve. Moreover, several accessions are duplicated across genetic resource centres. The format of the data should be standardized to facilitate easy access.

Could not agree more. Genebank data need to be much easier to access, preferably all in one place, like Genesys. That way researchers and breeders will know where they need to go to get the material they need, and what exactly they’ll be getting. Those fancy genomic tools won’t be much use if you can’t get hold of seeds. It’s through such use of genebank collections that the yield increases and the impacts on nutrition and environmental sustainability will come.

The authors of the paper don’t mention the Brazilian genebank in their table, but Arroz e Feijão has over 14,000 beans in storage. And, as I’ve mentioned here before, we at the Crop Trust are working with EMBRAPA to help them share their genebank data on Genesys. And not just beans, either. Yes, rice too.

The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the Crop Trust. The Crop Trust is committed to publishing a diversity of opinions on crop diversity conservation and use.