Erna Bennett: A Crop Diversity Maverick

8 April 2024

In this installment of our Seed Heroes series, we salute the Irish scientist Erna Bennett, whose unheeded calls in the 1960s to halt the rapid decline of crop genetic diversity are echoed in today’s global drive to save plant species from extinction.

Erna Bennett was a maverick whose ideas challenged the scientific consensus of her era but now look prescient amid international efforts to halt the biodiversity crisis.

More than 50 years ago, the Irish-born scientist was among the first to raise the alarm over the disappearance of crop genetic diversity, coining the terms ‘genetic erosion’ and ‘genetic conservation’ during the 1960s.

As a lifelong Communist and a one-time British spy who fought for Greek partisans in World War II, Bennett was used to being something of an outsider. This was no exception in her chosen field of plant genetics as she resisted the corporate interests behind much agricultural development.

After 15 years at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Bennett was forced to resign for criticizing its links to the agrochemical industry. In her view, big business was not only threatening rural livelihoods but also the crop genetic diversity of traditional farmers’ varieties—or ‘landraces’—in favor of genetically uniform plants bred for high yields.

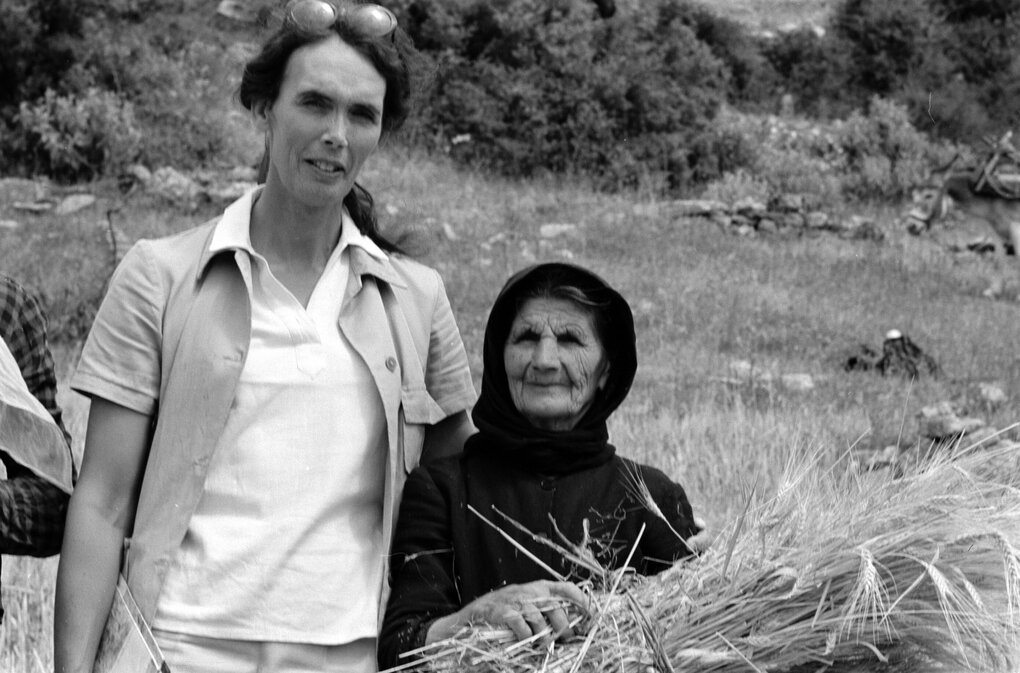

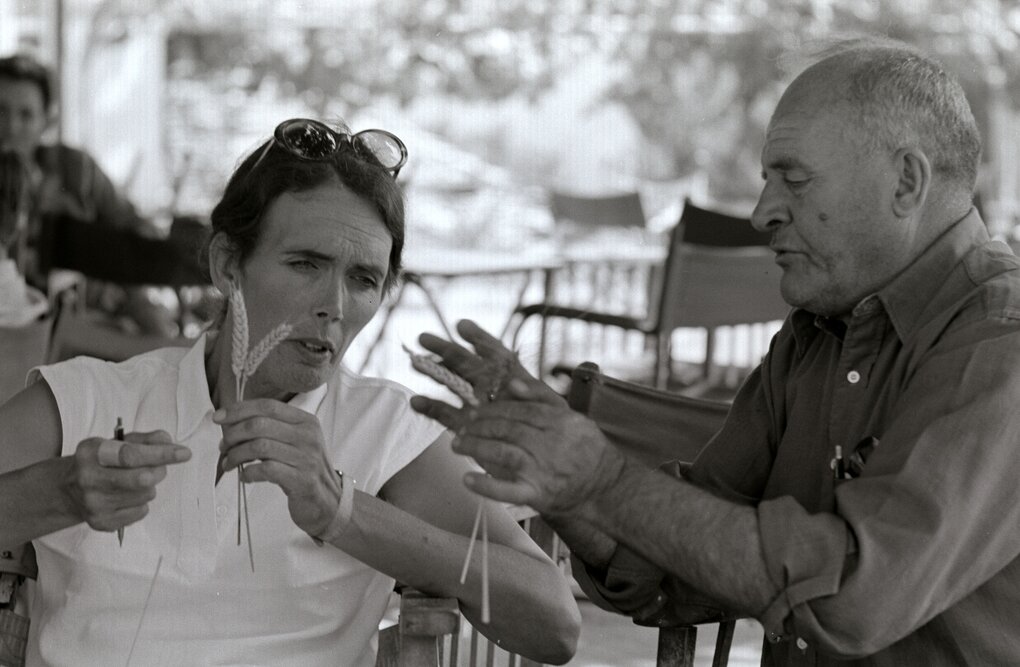

Erna Bennett on a FAO mission in Greece searching for and collecting primitive wheat varieties. Images of Erna Bennett courtesy of © FAO/Florita Botts

‘Impending Crisis’

In the early 1960s, Bennett recognized that the genes that were being mobilized to create the Green Revolution were causing an “impending crisis of global dimensions.”

“We began to realize that this process of erosion was a great deal more rapid than we thought because at that time the Green Revolution varieties were starting to spread, and these were really murderous in their effect on local diversity in the cereal crops,” Bennett said in a 1994 interview for an oral history project in Australia.

Bennett rejected the ‘all or nothing’ approach to pathogen resistance at the time, instead arguing that traditional farming allowed diseases to live in a “kind of equilibrium” with their host crops without devastating them.

Farmers’ Fields

She also advocated for the conservation of genetic diversity in farmers’ fields—where it evolves naturally in situ—and was skeptical of the “seed museums,” or genebanks, that large corporations were establishing ex situ for plant breeding programs.

“The purpose of conservation is not to capture the present moment of evolutionary time, in which there is no special virtue, but to conserve material so that it will continue to evolve. Such ‘continued evolution’ could only be possible in in situ collections,” she said at the FAO Technical Conference in 1967.

Today, the conservation of crop diversity relies on complementary in situ and ex situ efforts.

Bennett’s work also influenced the first world conference to focus on the environment—the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm—which called for a global program on the conservation of plant genetic resources.

Half a century later, the conservation of genetic diversity is widely considered to be key to a sustainable future and is enshrined in the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal to end hunger by 2030 as well as the Convention on Biological Diversity post-2020 framework, which was adopted in December 2022.

Erna Bennett on a FAO mission in Greece searching for and collecting primitive wheat varieties. Images of Erna Bennett courtesy of © FAO/Florita Botts

Early Years

Bennett was the eldest of four children, born in 1925 in the Northern Ireland city of Derry—officially Londonderry—before moving to Belfast at age 4. Her father was a police officer and a socialist who encouraged her to challenge prevailing ideas.

During World War II, she signed up to fight for the British allied forces despite being a year too young to enlist. After a stint in the aviation training program, where she was the first and only woman, Bennett drew the attention of the British intelligence service due to her ability to speak Greek.

After service in the Middle East and in Greece, she defected and joined the Greek partisans who were fighting the Nazis. It was here that she developed her strong political convictions, leading to her association with Communist parties in the UK, Italy and Australia in later years.

“I entered the Second World War as a rather timid, slightly stuttering, shy middle-class kid, and I emerged from it a Communist,” Bennett said in the 1994 interview in Australia.

Having developed an appreciation of traditional agriculture in Greece, Bennett studied botany at London University and then Durham University, graduating in 1953.

She worked as a waitress and then for the National Library for Science and Technology before landing a job at the Scottish Plant Breeding Station (a predecessor institution of the James Hutton Institute) under its director, Jim Gregor, who became her mentor and introduced her to the work of the Russian plant scientists Nikolai Vavilov and Evgeniya Sinskaya.

Breakthrough Papers

In 1964 and 1965, Bennett wrote two papers on genecology—a branch of ecology that studies genetic variation in species relates to the environment— which caught the attention of the FAO. She joined the organization two years later.

Along with her colleague Otto Frankel—who disagreed with her views on ex situ conservation—Bennett co-authored and edited the classic book “Genetic Resources in Plants,” which was published in 1970.

Bennett continued to publish influential papers, was an editorial board member of the FAO Plant Introduction Newsletter and conducted extensive collecting missions in Italy, Southwest Asia, Greece and Afghanistan. She was awarded the prestigious Meyer Memorial Medal of the American Genetic Association in 1971.

After leaving FAO in 1982, Bennett followed her partner, Pru Rigby, to Australia, where she wrote about politics, worked in the NGO sector and pursued her passion for poetry. She spent her final years in Italy and Scotland, where she died in 2012 at age 86.

Just like her hero Vavilov, whose views on agriculture led to his demise at the hands of the authorities in the Soviet Union, Bennett is remembered as a visionary whose work fell from favor in her own era yet is all the more relevant today.

Timeline:

- 1925: Born in Derry (Londonderry), Northern Ireland

- 1939‒45: Serves in World War II in British intelligence before defecting to Greek partisans

- 1953: Graduates with degree in botany at Durham University

- 1964‒65: Writes two papers on genecology while working at the Scottish Plant Breeding Station

- 1967: Joins FAO in Rome. Coins term ‘genetic erosion’ at FAO conference

- 1970: Publishes classic book “Genetic Resources in Plants” as co-author with Otto Frankel

- 1971: Awarded the Meyer Memorial Medal of the American Genetic Association

- 1982: Departs FAO in protest against corporate influence at the organization

- 1994: Returns to Scotland after years in Australia

- 2012: Dies at age 86 in Scotland