Is the System of Germplasm Sharing Global Enough Yet?

17 September 2015

25 years of international exchange of plant genetic resources: WHY The multilateral system needs a global management

- A Conversation between Luigi Guarino, Michael Halewood and Gea Galluzzi -

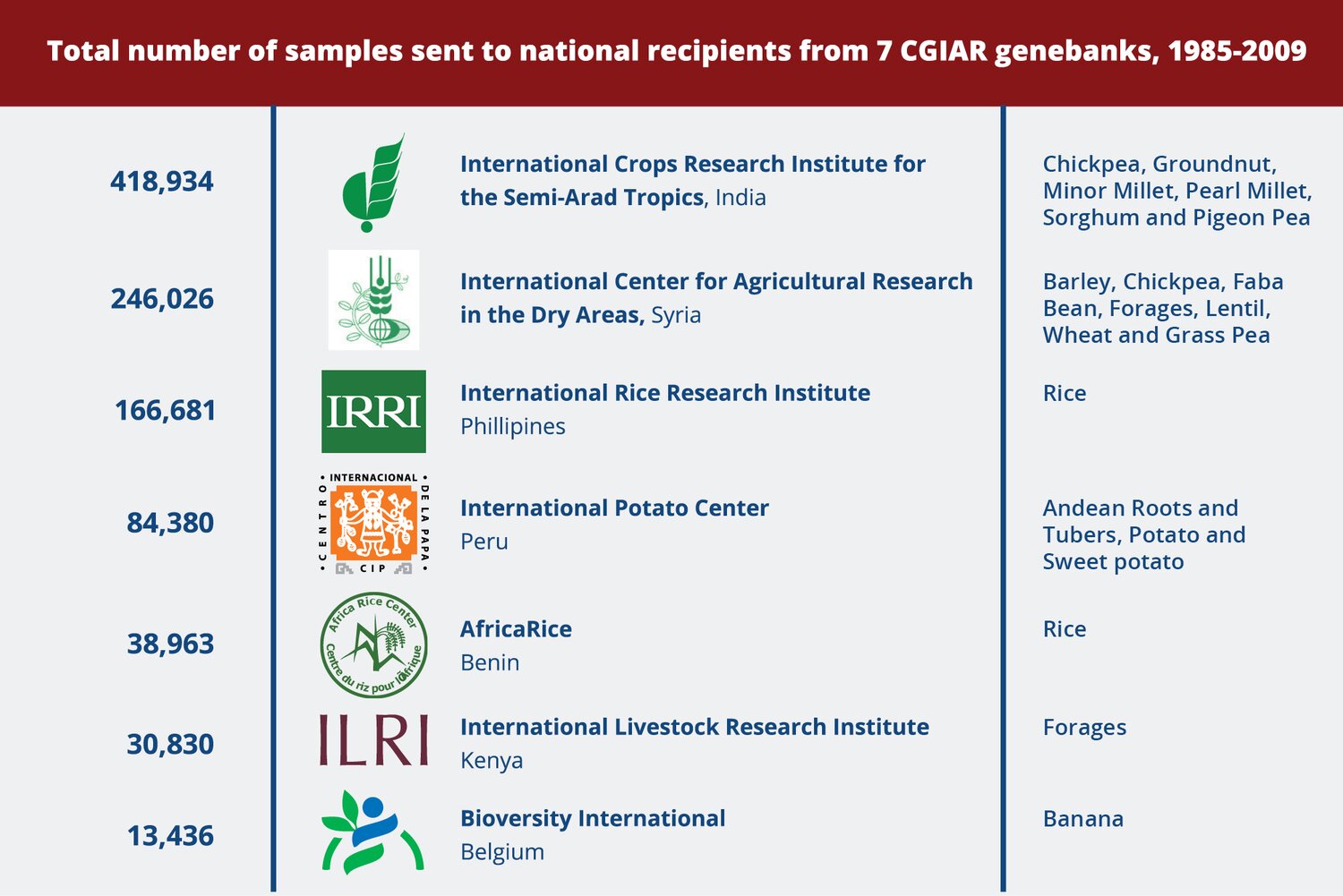

The research paper “Twenty five years of international exchanges of plant genetic resources facilitated by the CGIAR genebanks: a case study on international interdependence”, identifies global trends in the movement of Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (PGRFA) based on data from seven of the eleven international genebanks that the Crop Trust helps fund. The study deals with a substantial amount of data over a long period of time - close to one million samples were distributed by the genebanks of these CGIAR centers.

Wanting to discuss further the results of the paper, Crop Trust Senior Scientist, Luigi Guarino, spoke with two of the authors of the study: Michael Halewood, Head of the Policy Unit at Bioversity International, and Gea Galluzzi, a research fellow with Bioversity.

Luigi: What is the context in which the paper was published?

Michael: In 2013, a process was launched for renegotiating the terms and conditions of the Multilateral System of the International Treaty for PGRFA[1]. One of the purposes of this paper was to present it to the Ad Hoc Open-ended Working Group to enhance the functioning of the Multilateral System of Access and Benefit-sharing, which took place in June this year in Brasilia. There are two issues in particular that are being discussed in that context:

1) How to increase the amount of money that comes from users of the material in the Multilateral System (MLS) to the Treaty’s Benefit Sharing Fund.

2) How to increase the amount of material that is in the MLS.

People understandably tend to focus on the money. But it is important not to lose sight of the fact that the chief benefit of the MLS is facilitated access to germplasm – and that’s for everybody. So for this study, we concentrated on that particular issue, highlighting the extent to which people all around the world were already accessing and using genetic diversity through the facilitated system of access and benefit sharing.

Luigi: What would you say is the headline finding?

Gea: The magnitude and the diversity of the flows of germplasm, and the broad participation of countries in these flows. This is the primary message we wanted to transmit. And this flow has no correlation with the development status of a country or whether or not it is located in a center of origin.

Michael: The study effectively details, with extraordinary depth, the genetic material received in each country. Once the big numbers had been complied and studied, we then proceed to breaking these down in more detailed analyses.

Luigi: How big is the contribution of the CGIAR genebanks to the overall flow of germplasm around the world?

Michael: Based on recent estimates of yearly distributions by other important genebanks, it would appear that the CGIAR genebanks considered here facilitate international access to germplasm to an extent which is comparable only to the USDA’s National Plant Germplasm System. The numbers for the CGIAR the international system are considerably higher than the yearly average flows of other institutions such as the Russian Vavilov Institute or Embrapa in Brazil. Recent data shared by the ITPGRFA show that the CGIAR genebanks account for about 95% of the distributions reported to be occurring under a Standard Material Transfer Agreement (SMTA).

Luigi: Who is getting all this material?

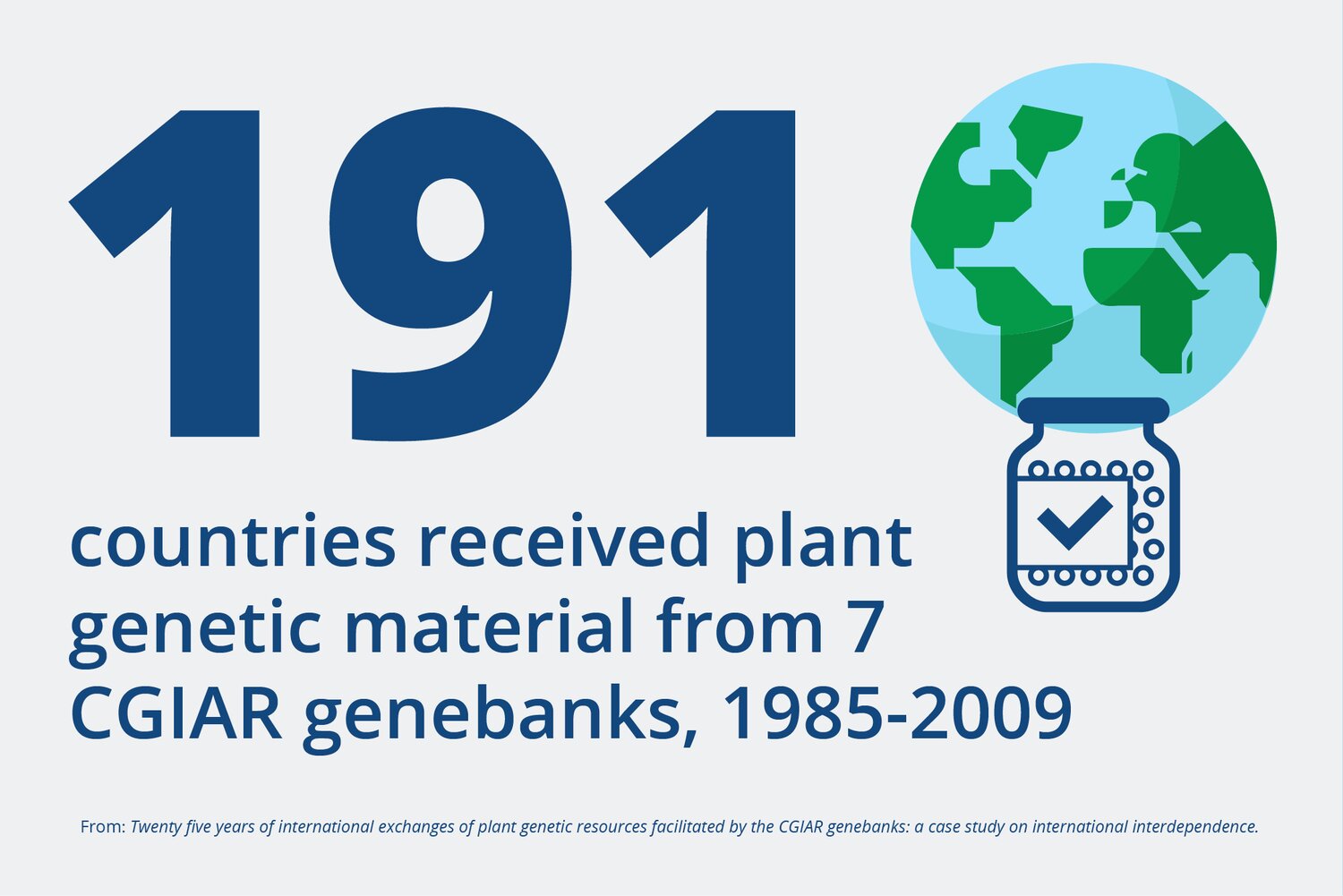

Gea: Every country in the world provided or received genetic resources through the system at some point during the time frame considered. By far most recipients are from the public sector – the dominant institutions being national agricultural research organizations and universities.

The Study not only confirms that countries are indeed interdependent, but presents new data that illustrates the magnitude and pattern of that interdependence. In the slideshow beneath some of the most important findings of the paper are displayed.

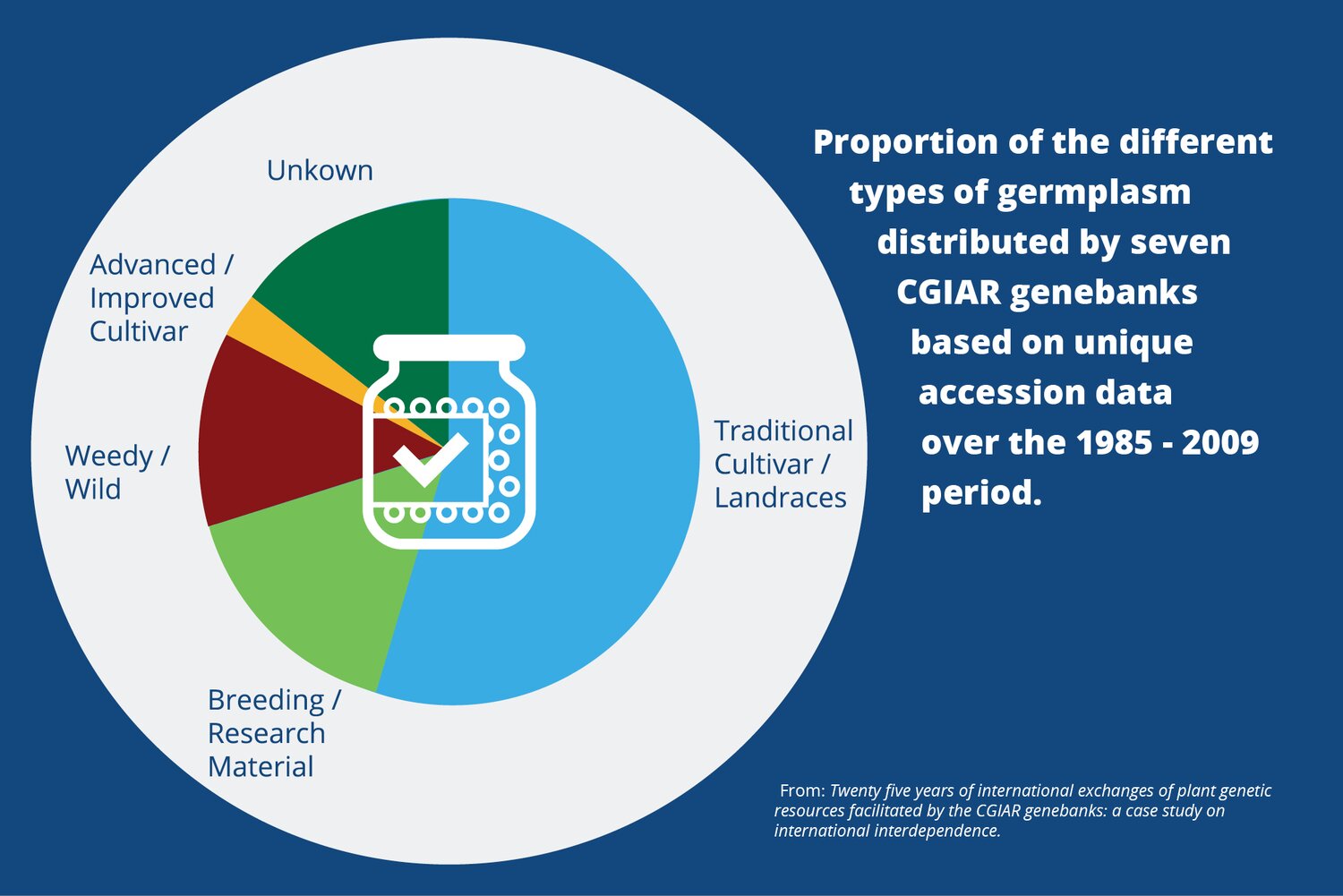

Global germplasm distribution, 1985 -2009: More than half of the material was made up of landraces and traditional cultivars. While less than 20% of the distribution was made up of breeding and research lines.

Any genetic resource can be used for research and development. Breeding and research lines are specific genetic resources usually with unique genetic or phenotypic properties which are used for specific breeding purposes. This relatively low percentage is due to the fact that genebanks prioritize conservation and distribution of "raw" genetic resources, not breeding materials, which are mostly conserved and distributed through breeding programmes.

“Improved cultivars are those genetic resources on which breeders have done a varying degree of improvement. The 7% figure, which is low, reflects the fact that CG genebanks usually give priority to landraces and wild relatives” - Gea Galluzzi.

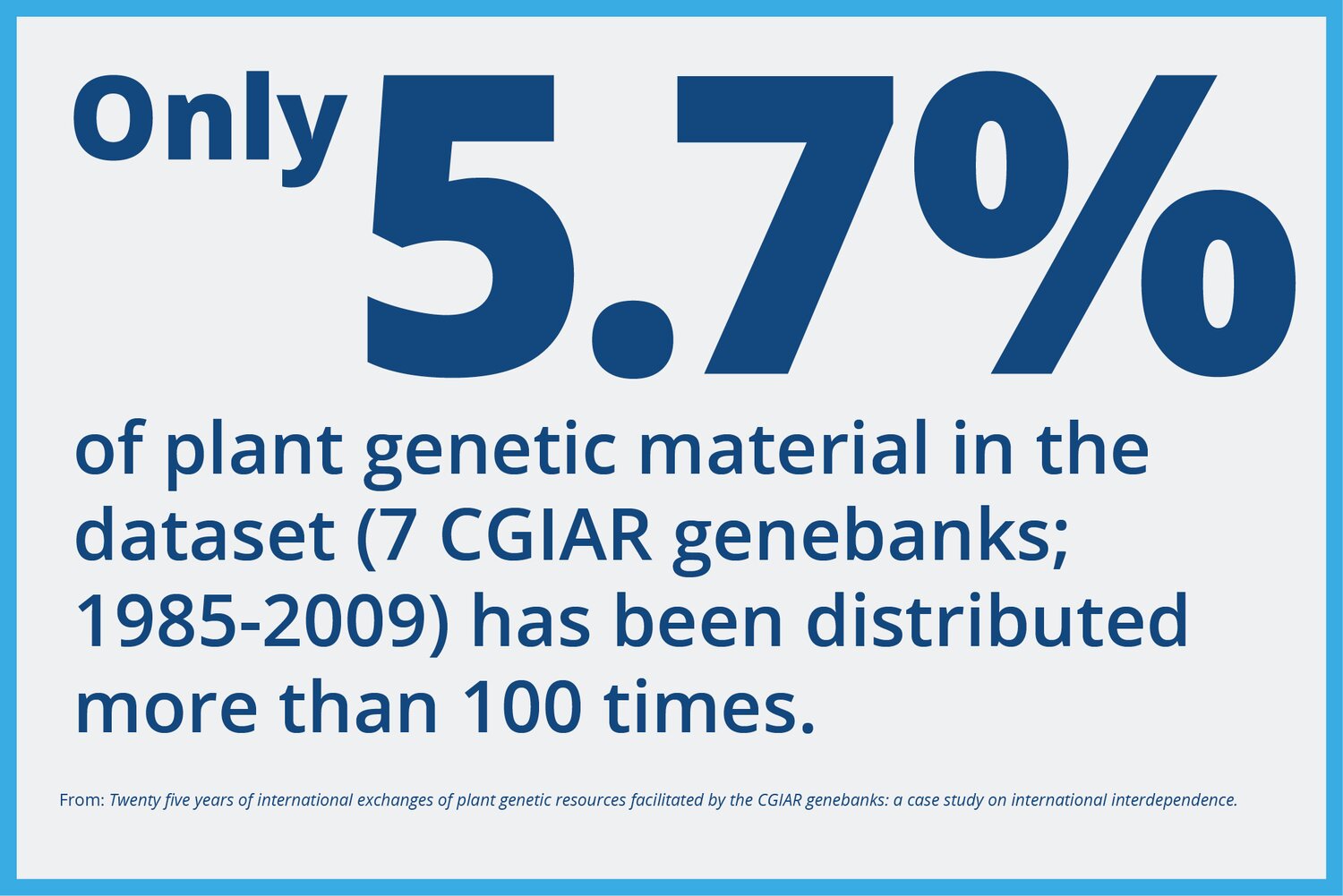

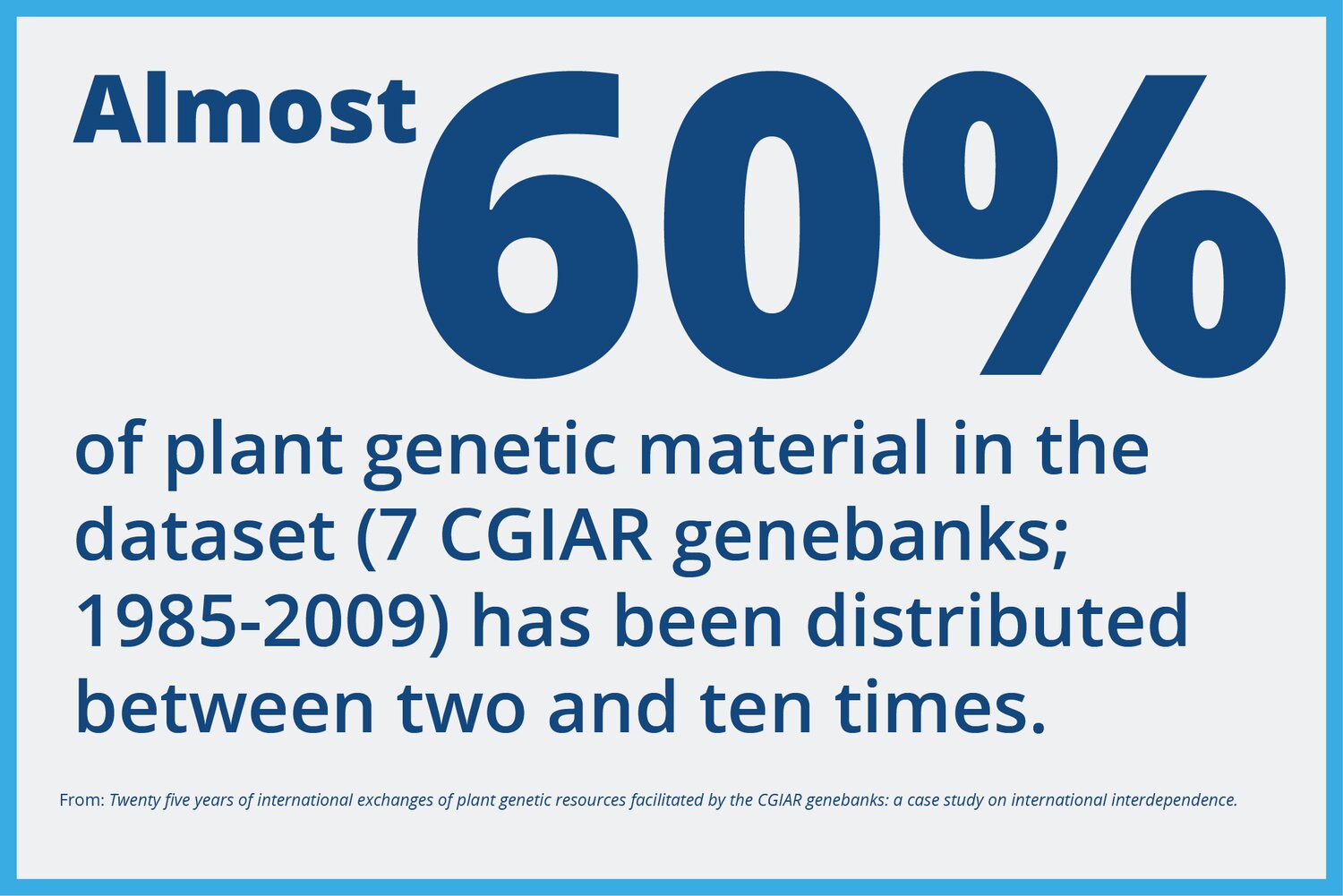

Though more than half of the plant genetic material conserved was been shared by these CG Centers in the 25 years analyzed, the repeat rate for most accessions remained low.

Material most frequently requested has for the most part been previously characterized, evaluated, and improved. This facilitates their use even in institutions and countries with limited capacities for carrying out the lengthy and costly breeding procedures needed to develop new crop varieties.

Virtually all countries in the world have been involved in the exchanges of plant genetic material: over 999,250 samples of 262,872 unique accessions belonging to 1,470 different plant species were distributed between 1985 and 2009.

The CGIAR center’s mandate crops include key staples for worldwide food security. The top three genebanks that distributed the most germplasm are located in Asia, and all safeguard and make available different grains, including wheat and rice.

Countries such as India, Ethiopia and the Philippines, which are centers of origin and / or diversity, have provided and requested a lot of material. E.g. Over 70 % of unique accessions originally collected in India went back to India, through the CGIAR-hosted collections.

Even diversity-rich countries, where centers of origin are found, are not self-sufficient in germaplasm and require significant amounts from the international genebanks.

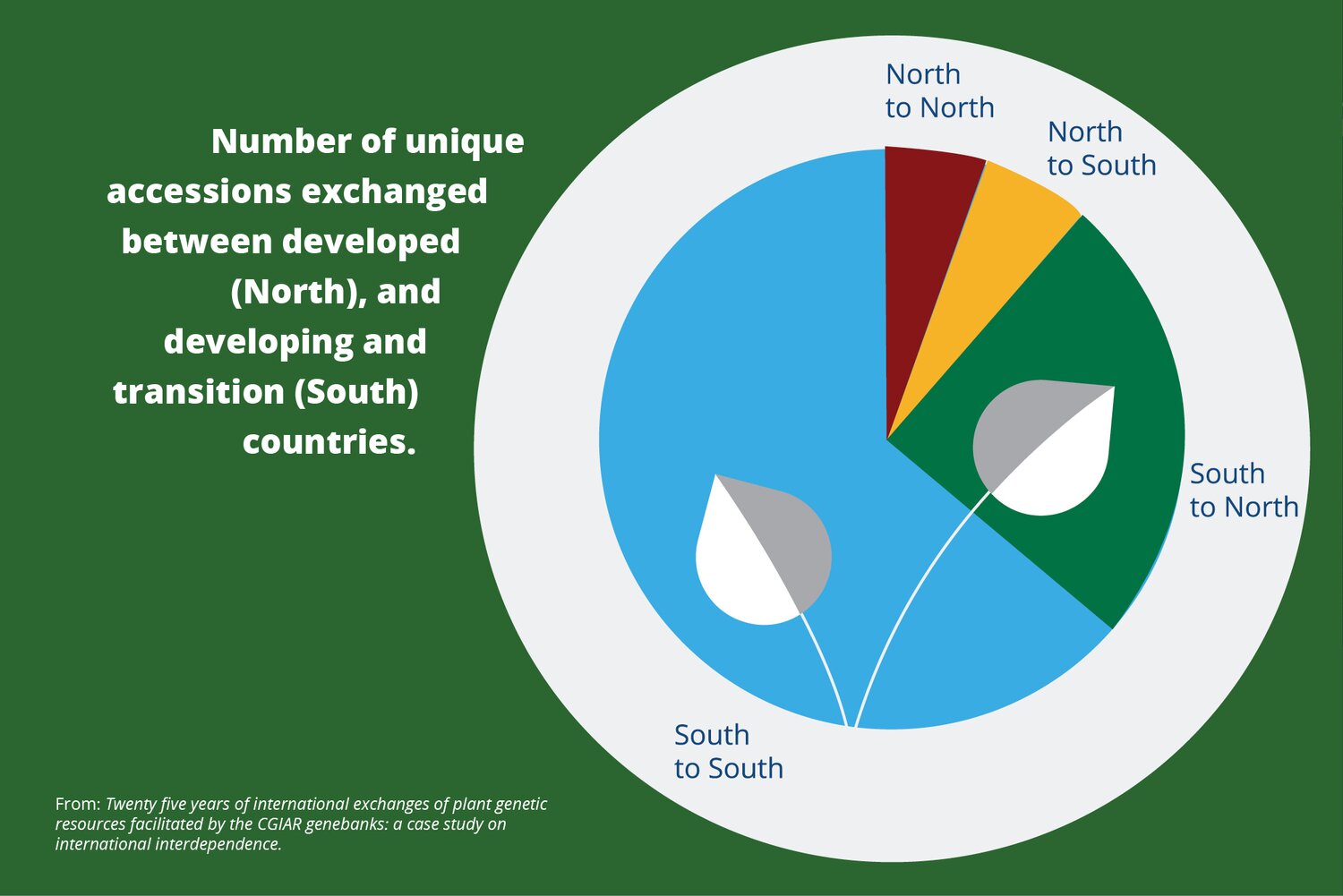

More than 60 % of the germplasm flows moved within developing countries. This is not surprising, considering the population and total size of the developing world, and the fact that these countries harbor the larger part of crop diversity.

Apart from the priority given by CG genebanks to landraces in their collections, users may be giving them special attention in their requests because of the diversity they harbour, which is generally higher than that contained in materials with a more formal improvement process.

Michael: According to the data, India came out as both the top provider and the top recipient of genetic material. Interestingly, most of the material India asked for was originally collected in India. And this is despite the fact that India has a fairly large national collection. The CGIAR Centers still play an important role in storing and making available material from a country whose National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources (NBPGR) and other institutions have considerable capacities. And that’s something that probably hasn’t been picked up by other studies.

Gea: However, India in this regard serves only as an example for a general trend!

Luigi: India and other countries that have great biodiversity, such as for example Ethiopia and the Philippines, have increasingly been benefitting from that same system to which they’ve been providing?

Gea: Yeah, this is clearly seen in the list of top 10 providers and recipients. Another great example is the United States.

Luigi: Tell me about the balance between private and public sector users.

Gea: Public sector recipients make up the vast majority in all countries. There is a pretty small share of private sector recipients, accounting for just 3% of the total.

Michael: And it’s interesting to mention that the great majority of the transfers to the private sector (2.3 %) are in developing countries.

Luigi: Why do you think that is? Why isn’t the private sector making more use of the CGIAR Centers genebanks?

Gea: I think it has something to do with the modus operandi of the CGIAR Centers. Historically, they have mostly worked with agricultural research organizations and public institutions in developing countries. That has been the mandate of the centers and their collections. Over time, this may change as private-public partnerships develop.

Luigi: Are there any other interesting conclusions that you have drawn from the data?

Michael: I was quite surprised to see that many countries have received quite a large amount of material. The top 25 recipient countries for the years 1984-2009, had received genetic material from 102 other countries. That’s just bigger than I thought, and bigger than I read before!

Luigi: The system is truly multilateral, isn’t it? In the sense that everybody has been contributing to it over the years and everybody, similarly, has been benefiting from it over the years?

Michael: Absolutely. The MLS can still be improved in many ways. All country members of the Governing Body agreed unanimously to open the negotiations up again, readjust the deal and the system. If ever there was a time to marshal the evidence of the benefits of facilitated access that have accrued through the system, bringing it to people’s attention, and reaching out to countries, now is the time.

Current and future challenges in agriculture and food security - such as climate change and a growing world population - will increase demands from the world’s genebank collections. The data on international flows of genetic material show the inevitable interconnectedness of agriculture. As the multilateral system continues to evolve, the Crop Trust will continue to play a key role in developing a truly global system for ex situ conservation to ensure its long-term survival.

[1] On ratifying The International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA) countries agree to make the genetic diversity of 64 crops which is under their management and control available under specific facilitated conditions through the Multilateral System (MLS).

Text: Konstantin Zell

Categories: Food Security, Nutritional Security, Sustainable Agriculture