Plan B for Backup: Sweetpotato Seeds Go to Svalbard

19 February 2025

There’s a sweetpotato variety in Papua New Guinea called “Gimane.” But farmers prefer to call it “I don’t care.” Gimane earned this name because it doesn’t care – it grows well with almost no inputs, making it a hassle-free crop. After they plant Gimane vines, farmers barely need to care for them. In four to five months, they get a decent harvest.

Gimane is just one of perhaps 5,000 sweetpotato varieties in Papua New Guinea, and researchers from the country’s National Agricultural Research Institute (NARI) genebank are hoping to conserve them all, forever. With support from the Crop Trust, that now includes doing so in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in the Arctic.

Commercial sweetpotato farmer Anton Kua in the Asaro Valley at Meteiyufa village shows off the Gimane variety he has planted on his farm. Photo: Mike Major/Crop Trust

Sweetpotato Diversity in Papua New Guinea

Sweetpotatoes likely arrived in Papua New Guinea 400 years ago, and in that relatively brief time they have become an incredibly diverse and important crop there.

Sweetpotato accounts for a large percentage of the calories in Papua New Guinean diets, especially in the highlands. It is also a leading cash crop in domestic markets for smallholders.

“Due to the favorable and diverse growing conditions and the degree of farmer selection, an enormous amount of diversity of sweetpotatoes has developed here in a relatively short period of time,” says Birte Nass-Komolong, a program director with NARI. While sweetpotato originated in Central and South America, where its diversity developed and evolved, “Papua New Guinea is considered a secondary center of diversity for the crop,” explains Birte.

Because sweetpotato is vital for nutrition and incomes in Papua New Guinea, preserving its diversity is crucial.

“We’ve noted a high loss of genetic diversity among the sweetpotatoes in farmers’ fields across the country,” said Birte. “That’s primarily due to the shift from subsistence farming to commercial farming, environmental degradation and increasing pressures on land.”

So NARI supports local efforts to conserve that diversity. That includes the NARI genebank, which manages one of the largest collections of sweetpotato in the world, with 865 different types.

Some of the 530 sweetpotato varieties in the regeneration plot at NARI’s Aiyura station in Eastern Highlands Province. Photo: Mike Major/Crop Trust

Plan B for Backup

Sweetpotato is grown from cuttings, not seeds. That means conserving it is more complicated than is the case for rice or wheat. At NARI, sweetpotato diversity is stored either in the form of fully grown plants in a field genebank or as tiny plantlets in test tubes in the lab, also known as in vitro.

NARI conserves sweetpotatoes in vitro at its Aiyura facility, but this collection is costly to maintain. Photo: Mike Major/Crop Trust

“Both of these options are pricey, labor-intensive and risky,” says Boney Wera, a crop breeder with NARI. “It’s challenging for a country like Papua New Guinea to maintain its enormous sweetpotato diversity. To safeguard this crop diversity for future generations we need complementary methods.”

The Crop Trust stepped in to help. The Biodiversity for Opportunities, Development and Livelihoods (BOLD) supports NARI with a plan B to back up sweetpotato diversity as seeds. In the appropriate conditions, sweetpotato seeds can survive up to half a century and still germinate, making this a highly practical method for conserving sweetpotato diversity.

“This approach is quite different from field genebanks or in vitro,” says Birte. “By conserving sweetpotatoes as seeds, we are conserving genes rather than varieties.”

Conserving sweetpotato as seeds does not preserve specific varieties. This means that if you grow plants from the seeds of a variety like Gimane, the new plants and their tubers won’t be identical to the original Gimane plant.

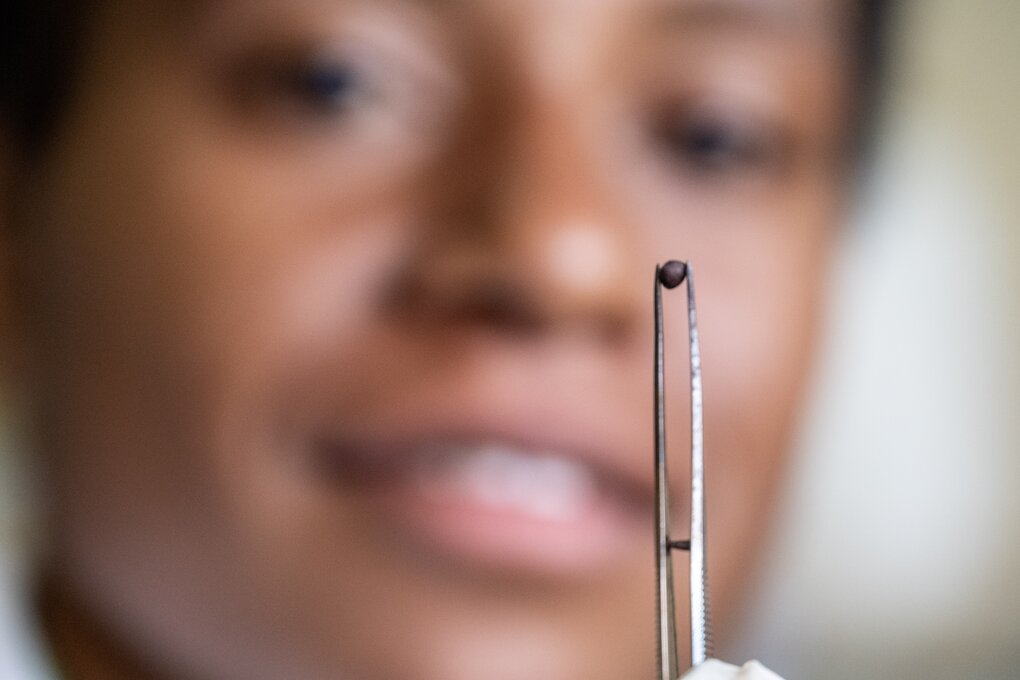

Crownie, a trainee student from PNG University of Technology (Unitech), holds a single sweetpotato seed, which could hold the genetic material required to develop sweetpotatoes that are resilient to climate change. Photo: Mike Major/Crop Trust

Think of genes as ingredients in a recipe. Put them together in particular proportions and you get a unique variety, like Gimane. Plant a vine of Gimane, and you get the same recipe. But get Gimane to set seeds and you are shuffling the ingredients around. All the genes that went into making Gimane what it is are there in the seeds, but not in the exact combination that gives you Gimane. It’s the same reason why human siblings look similar but not identical. Unless they’re twins, of course. Twins are more like two vines from the same sweetpotato variety. Not exactly, but you get the picture.

Anyway, the point is that breeders can still use the genetic diversity stored in seeds to develop new and improved sweetpotato varieties in the future, ensuring adaptability and resilience. Even if Gimane is lost in farmers’ fields, they would still be able to find the characteristics that make it so special. The genes are still there, hidden in the seeds.

Collecting Seeds to Store Forever

Collecting seeds from sweetpotatoes presents a number of challenges.

“You need flowers to produce seeds and not all of the plants in our collection produce flowers,” says Birte.

So NARI induces flowering in some of those difficult varieties with tricks like spraying them with gibberellic acid, a plant hormone that promotes growth, or exposing the plants to stress by watering them less. Researchers also use bees to facilitate pollination.

Bonopa Uto collecting seeds from a plant in the sweetpotato regeneration plot at NARI’s Aiyura station in Eastern Highlands Province. Photo: Mike Major/Crop Trust

Once collected, the seeds are dried and conserved at low temperature at NARI to maximise how long they will remain viable. They are also sent elsewhere for safety duplication.

“A duplicate will be sent to the Centre for Pacific Crops and Trees (CePaCT) genebank in Fiji for first-level backup storage,” says Beri Bonglim, the manager of BOLD’s Regeneration and Safety Duplication work.

As a second level of security, BOLD helped NARI send safety duplicates to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. This was Papua New Guinea’s first-ever deposit into the Vault, which is the ultimate backup for the world’s crop diversity.

As the climate changes, we should all care that the genes that make “I don’t care” so desirable will always be there, on some cold shelves in the Arctic.

Since 2021, the Crop Trust has worked with 42 partners worldwide to regenerate and safeguard vital seed collections. Through the BOLD Project, these partners ensure that key crop diversity remains alive and thriving in genebanks, backed up in another location, and secured for the future in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. With support by the Government of Norway, this essential work strengthens biodiversity, food security and resilience for generations to come.

This story is one of many about the dedicated partners who have worked for years to regenerate seeds and send them to Svalbard for safekeeping.

Categories: For The Press, For Partners, BOLD, Food Security, Nutritional Security