Encouraging Curiosity: Jonathan Drori and The Stuff that Stuff is Made Of

26 August 2025

From ancient Peruvian popcorn to lightning-resistant beech trees, Jonathan Drori has a knack for uncovering the surprising ways plants shape human history and culture. A former BBC filmmaker and trustee of Kew Gardens, Drori is perhaps best known for his bestselling books highlighting the role of plants in human life and culture – Around the World in 80 Trees and Around the World in 80 Plants.

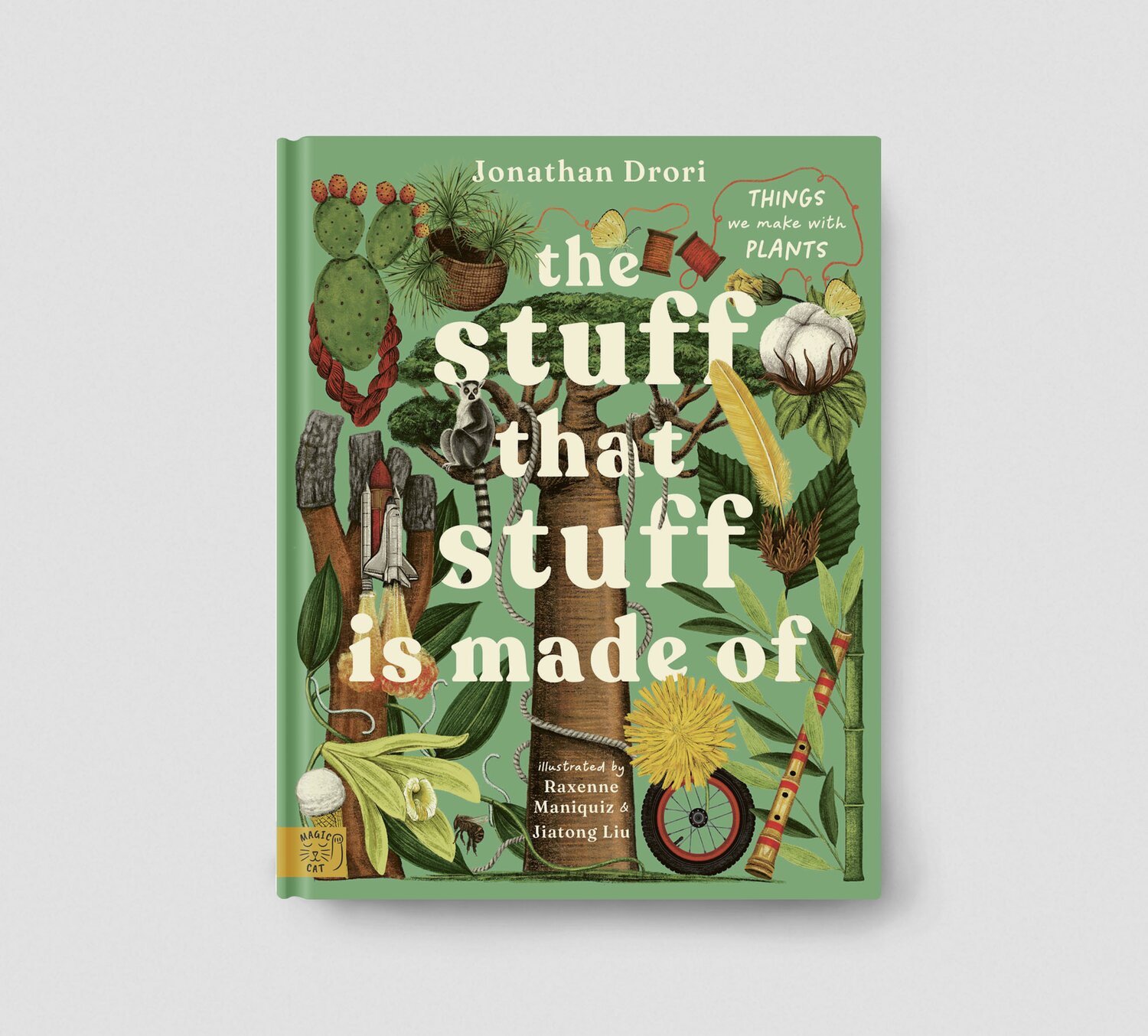

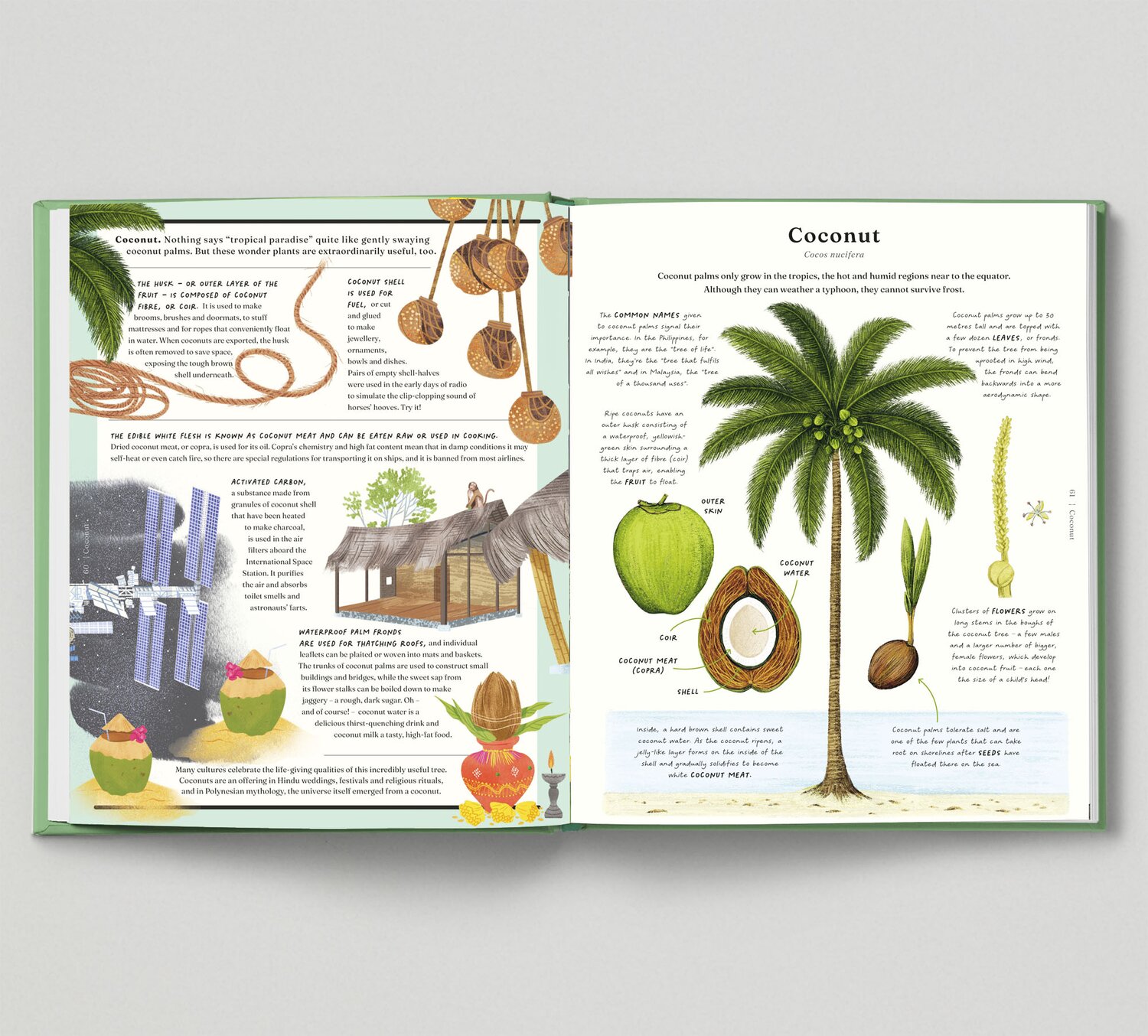

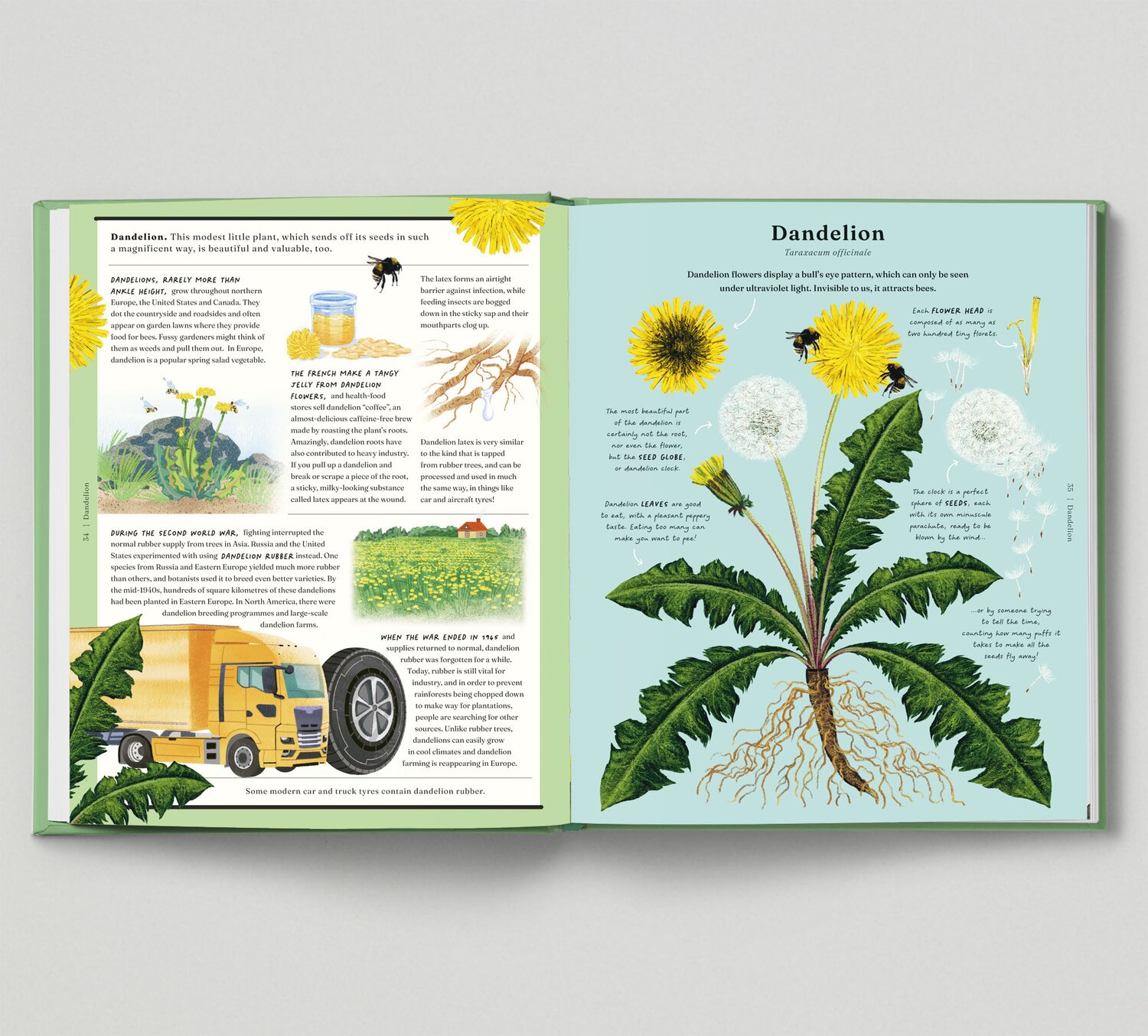

With his latest book, The Stuff that Stuff is Made Of, he turns his attention to younger readers. Leafing through it, children – and indeed their parents – will discover 30 special plants from baobab trees to tomatoes – how they grow, why they matter and the things we make with them. Fascinating stories along with intricate illustrations by Raxenne Maniquiz and Jiatong Liu offer a new perspective on why protecting crop and plant diversity matters more than ever.

We sat down with the author to learn more.

Crop Trust: Thanks for joining us, Jonathan. Tell us about The Stuff that Stuff is Made Of, your first book for kids.

Jonathan Drori: Things can only get better if young people learn about plants and care about them from an early age. The book has two audiences, really. There are the kids – eight to twelve year olds – who I hope will enjoy it, and that's the primary audience. But there's also the adults around them. Many adults are indifferent to nature, consume products without reflecting where they or their ingredients came from, and don’t spare much thought for biodiversity or climate change... If you can reach those adults through their children, while they're explaining the book to them, that's a terrific way of changing people’s attitudes.

Crop Trust: You’ve spoken about going to Kew Gardens when you were a child. As you were writing this book, did you travel back to that time?

Jonathan Drori: Yes, very much so. I try to encourage curiosity with my writing. My parents managed to encourage my curiosity at Kew Gardens. It wasn't just my father, who was really interested in science and botany, but also my mother, who found the aesthetic side of plants fascinating. Neither of them were terrific gardeners, but they both loved plants.

My father especially would get us interested by feeding us bits of plants as we went around. I remember him putting a tiny bit of opium poppy latex on my tongue, asking, “Can you feel anything?” As a child I’m pretty sure I said yes, though in my memory it just felt like a tiny bit of something. It had a much bigger effect on my schoolteacher when I told her! Between them, my parents told my brother and me stories about history and culture connected with plants – from slavery and punishment plants like Dieffenbachia to cooking and science, fun and folklore. Each plant had a story. That's the spirit I wanted to capture in my books.

Crop Trust: And so the stories of 30 plants are in the book. What are some that didn’t make it?

Jonathan Drori: Well, some plants are economically important – like oak – with many historical stories. But there wasn’t space for everything. Others might be very important in one part of the world, like certain West African medicinal plants, but didn’t have enough resonance around the world. I wanted reasonably mainstream plants, but with quite a few surprises. And I have tried to ensure that even well known plants, such as maize, rice and rubber have surprises on every page, even for adults.

Crop Trust: And which of the 30 would be your favorite, and why?

Jonathan Drori: It’s really difficult to choose! There are favorite plants, and then favorite entries in the book – and they’re not always the same. I love that the beech tree, for instance, is better able to survive lightning because of its smooth bark: during rainstorms, water runs down in a continuous sheet, acting as a natural lightning conductor.

I also love the fact that Peruvians were making popcorn thousands of years ago, casting it on water as an offering to please the gods. Or cocoa – when you think about the long, complex process from pod to drink, it must have been discovered almost by accident. Some plants are so bitter or poisonous – cassava, for example – that you wonder how anyone figured out how to make them edible. Likely it was years of trial and error, and watching what animals ate.

Crop Trust: Are there examples of domesticated plants that stood out in your research?

Jonathan Drori: Yes, definitely. It’s incredible that maize started as a tiny wild grass – teosinte – with small, triangular seeds. In Mexico today there are dozens of varieties, with different shapes and flavors and textures. Yet in UK and US supermarkets we mostly know one type, yellow and sweet, but perhaps a little boring? The same with rice. In Britain people might recognize pudding rice and one kind of long-grain rice. But in Vietnam, say, or Madagascar, there are countless types, each with its own place in culture and daily meals.

Crop Trust: But do you see some diversification happening in the UK?

Jonathan Drori: In big cities like London, thanks to immigration, we do see more variety in specialty food shops – different kinds of rice and corn, spelt flour alongside wheat, cassava, plantains... But outside cities, variety depends on demand. And that’s often rather limited.

England has a tradition of apples, so people here recognize many varieties of apples. But with big staple crops – wheat, rice, potatoes, maize – there isn’t so much diversity in our stores. It’s getting better, but not fast enough. We need supermarkets to push variety more, but for that to happen there has to be consumer demand. Supply and demand need to be addressed together.

Crop Trust: Speaking of crop diversity, you visited Svalbard. What were your impressions?

Jonathan Drori: I think what the Crop Trust does is so important. The Svalbard Global Seed Vault is the tip of the iceberg, excuse the pun. Crop diversity is essential not only for food security but for the sheer joy of its existence! I was immensely proud to be part of that Crop Trust event. The trip itself was wonderful – although surprisingly not as cold as I’d imagined! The people I met there were just fantastic.

I was on the board of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and so I was involved with the Millennium Seed Bank. That’s different – it’s not a crop genebank but rather focuses on wild species. It complements crop collections like those backed-up in Svalbard. I’ve also been on plant collecting missions, often as a filmmaker – helping organizations tell their stories.

Crop Trust: How can scientists better share the stories behind their work?

Jonathan Drori: A good way to start communicating science is to listen, no, really listen, to your audience. What do they know, or think they know already? By working with that, rather than sticking to a pre-prepared ‘script’ there’ll be a better chance of changing minds. Of course, explaining why your work might matter to the person who’s listening is vital but you have a much better chance of finding out what matters if you ask them questions and listen to their answers!

Have enough confidence to put things in plain words. Use analogies from the worlds of your listeners. Scientists are trained to remove emotion and speak in a passive voice – “this was done” rather than “I did this.” But audiences connect with emotion and personal perspective. Scientists sharing their feelings, their excitement and indeed frustration, makes the communication much, much more powerful. Above all, share your curiosity and encourage your audiences to be curious too!

I hope that’s what I’ve done with this book, share my excitement and curiosity about plants, so that both children and adults will want to learn about them, and protect them.

Jonathan Drori’s The Stuff that Stuff is Made Of will be published by Magic Cat Publishing and available from all booksellers in the UK, US and Australia on September 25th 2025, and worldwide in translation soon afterwards. Jonathan donates his UK proceeds to Kew, the WWF and some smaller eco-charities.

Categories: For Partners, For Students