2017 Olam Prize for Innovation in Food Security Goes to Filippo Bassi and Team

14 December 2017

There are two ways you can deal with a problem. You can try to out run it. Or you can run towards it. Both have their advantages. Running away from a problem sounds bad, but discretion can indeed sometimes be the better part of valor. Look at the problem crops have with climate change. In some parts of the world, conditions are going to get so hot or dry for some crops, and so fast, that the easiest thing will be for cultivation to simply move to other places.

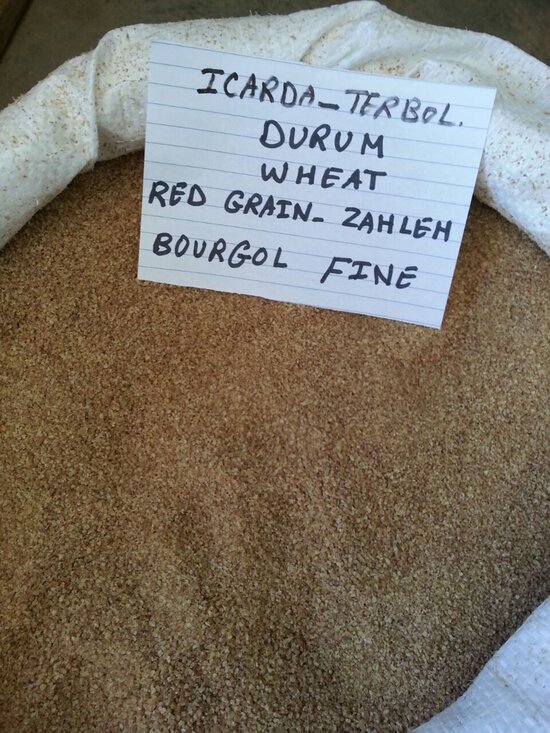

That’s not Filippo Bassi’s style, though. He’s the type that runs towards the problem. A durum wheat breeder based at the International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) in Morocco, he decided to use the diversity of his crop to develop new varieties for a place so hot that the crop already struggles there. And that’s not all. He wanted them to grow fast too.

The place is the basin of the Senegal River, which covers parts of Senegal, Mauritania and Mali in West Africa, home to at least a million families. Their main staple crop there is rice, but no cultivation is possible for 4 months of the year – December to March – because it’s too cold at night. Which is why the new durum varieties would come in handy. They would provide income and nutrition at what is otherwise a difficult time of the year, a hungry time. The problem is that during the day temperatures can reach 40°C. That’s very hot for durum wheat.

Crazy?

Even Filippo thought so, at the beginning. But fast forward five years of looking through thousands of different lines of durum wheat and its wild relatives, from genebanks and elsewhere; and making thousands of crosses among them; and looking at thousands more of the resulting offspring; and repeating the whole process again. It’s been hard, hot work, but Filippo and his team have come up with new varieties that show great promise, with the potential to yield three tonnes per hectare in just 90 days. They will now work with the pasta and couscous industry to make growing them profitable.

The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the Crop Trust. The Crop Trust is committed to publishing a diversity of opinions on crop diversity conservation and use.