Breathing New Life into the Global Crop Conservation Strategies

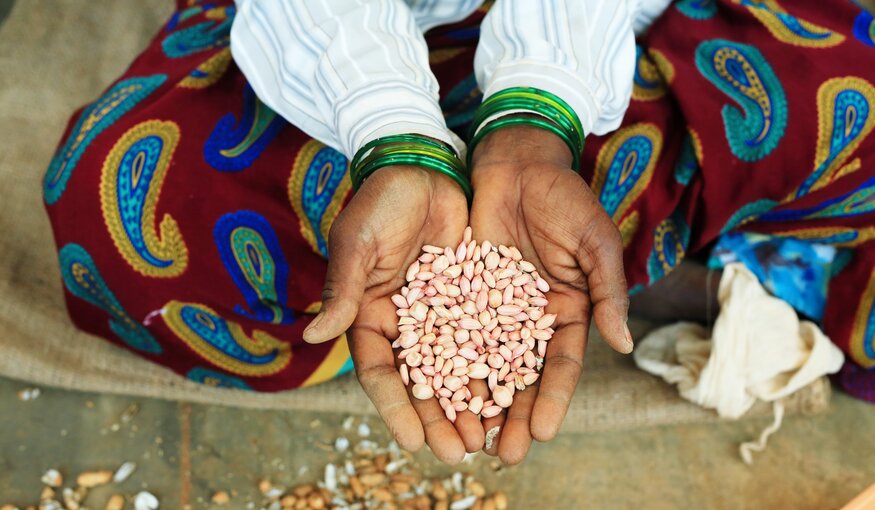

18 December 2019

A Strategy Is a Plan You Make To Achieve a Defined Goal

Our goal at the Crop Trust is to help ensure the long-term conservation and availability of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture. To achieve this ambitious goal, you have to know what’s in individual genebanks. But you also have to look across genebanks, crop by crop. For the past 15 years, the key mechanism for doing this has been the global crop conservation strategies. These take stock of where we are in terms of conserving and making accessible crop diversity by recognizing that the specific actions needed to underpin the conservation of different crops may differ significantly, depending on the biology of the crop, on the representativeness of current collections, and on the degree to which these are managed according to international standards.

Enter the Global Crop Conservation Strategies

Over the past decade, the Crop Trust has facilitated the development of 26 global crop conservation strategies by crop experts and other stakeholders around the world. The strategies describe the current status of conservation of major collections, and they attempt to identify the highest priority activities and resources required to safeguard the diversity of different genepools.

The Governing Body of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA) has recognized that these strategies are key guides for the development of a truly efficient and effective global system of ex situ conservation.

To stay relevant, however, the strategies need to be continuously updated with any relevant new information that becomes available on the make-up and status of collections, and the genetic structure within crop genepools. Some of the existing strategies are ten or more years old. A lot has changed since they were first put together.

Providing an Evidence Base for the Global System of Ex Situ Conservation

That’s why, in the past few months, the Crop Trust has started a new three-year project, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BMEL) . This will update five of the existing global crop conservation strategies that have been identified by a group of expert as most in need of revamping (potato, yams, Vigna, millets and sorghum), and also deliver 10 new strategies, for groundnut, pea, cucurbits, temperate forages, sunflower, eggplant, peppers, vanilla, Brassicae and Citrus.

To do this, the Crop Trust will coordinate and facilitate the work of “crop communities” composed of crop experts, genebank staff, and other relevant stakeholders. The project will update data on the accessions conserved in genebanks around the world by accessing information through the Global Information System on PGRFA (GLIS), Genesys, country reports to the Global Plan of Action for PGRFA (GPA) monitoring process, and also through custom-built surveys.

A key component of the strategies will be a quantitative gap analysis. For each crop or crop group, we want to be able to answer the question: What’s missing from the world’s genebanks? We will use the result of three complementary approaches that have been developed over the last two years by the CGIAR-Crop Trust Genebank Platform.

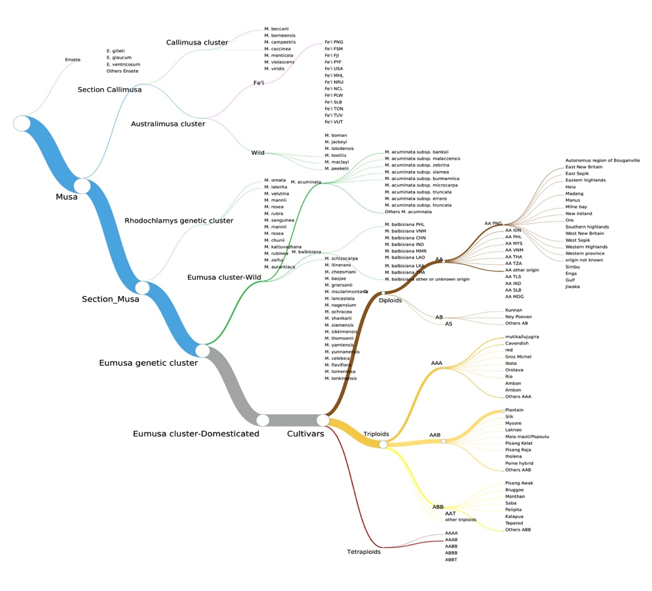

“Diversity trees” will be the main tool we will use (Figure 1). These are a representation of the genetic diversity within a crop genepool obtained by dividing the genepool into hierarchical clusters according to expert knowledge (a methodology developed by Van Treueren et al., 2009). They can help visualize the representativeness of genebank collections, identify gaps and thus priorities for further collecting, and highlight complementarities among collections, and thus opportunities for rationalization.

Figure 1. Banana genepool diversity tree. A diversity tree is a representation of the overall structure of diversity within a genepool obtained by dividing it in a hierarchical manner. The structure of the tree is based on published information and consultation with experts.

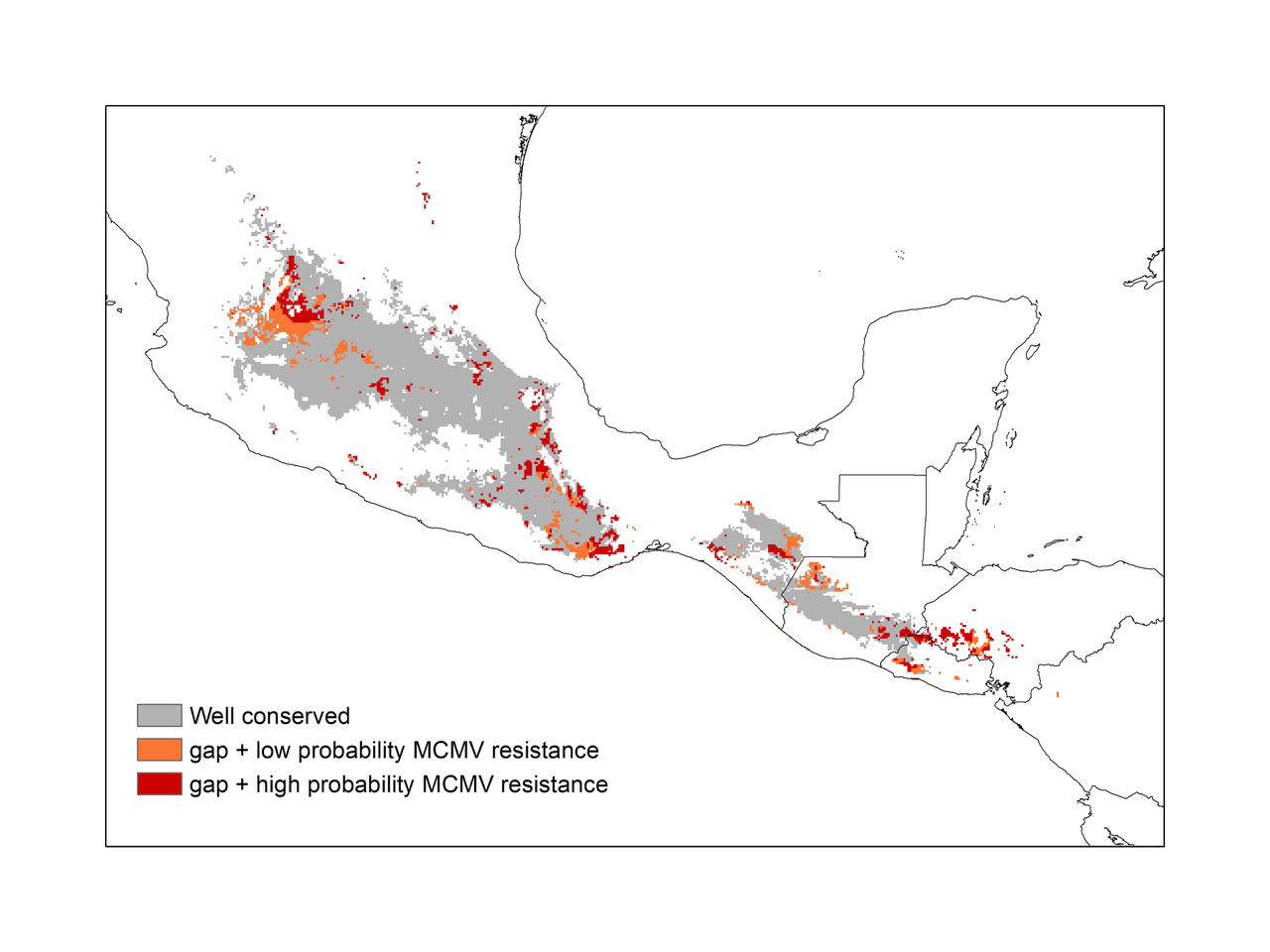

We will also use the results of spatial analysis of the ecogeographical coverage of collections of landraces, and of the predicted distribution of priority traits, to identify regions that are either gaps in existing collections or where traits of interest (for example resistance to a specific disease) are most likely to occur (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Overlay of predicted gaps for highland maize overlaid with probabilities of occurrence for resistance to Maize Chlorotic Mottle Virus (MCMV).

Toolkit

In addition, the CWR Project, ‘Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change: Collecting, Protecting and Preparing Crop Wild Relatives,’ has completed a global gap analysis for 85 crops to identify the crop wild relatives taxa and geographic areas which remain a priority for further conservation action (Castañeda-Álvarez et al 2016).

Finally, CIAT will soon publish a new study, carried out in partnership with the Plant Treaty, providing baselines and a set of indicators for around 350 plants contributing to global food security and sustainable agriculture.

Pulling all this information together and making sense of it will be the job of the Global Crop Conservation Strategies.

The new and updated strategies will make use of up to date knowledge and information to help plan and prioritize actions to ensure the long-term conservation and availability of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture. At the end of the project, we will reflect on what we have learned during its implementation, and, in partnership with the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA), we will recommend a dynamic system for developing, implementing and updating crop conservation strategies beyond the timeframe of project itself. We will then have not just the strategies themselves, but a strategy for sustaining them, if you will.

The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the Crop Trust. The Crop Trust is committed to publishing a diversity of opinions on crop diversity conservation and use.

Literature cited:

Castañeda-Álvarez, Nora P., et al. “Global conservation priorities for crop wild relatives.” Nature plants 2.4 (2016): 16022.

Van Treuren, R., et al. “Optimization of the composition of crop collections for ex situ conservation.” Plant Genetic Resources7.2 (2009): 185-193.