Landrace Conservation Offers Hope in Race to Collect Crop Diversity

9 May 2022

Crop diversity –alongside soil, water, sunshine, and hard work –is the foundation of agriculture. It keeps crops productive and nutritious, provides resilience against pests and diseases, and gives us the potential to adapt to climate change.

Yet a huge amount of this diversity, including hundreds of thousands of traditional farmer varieties (often called landraces) once grown in farmers’ fields, is no longer cultivated. The reasons are complex –both social and environmental. Everything from mega trends of economic development, globalization and urbanization through to local challenges such as droughts, unhelpful agricultural policies and civil unrest.

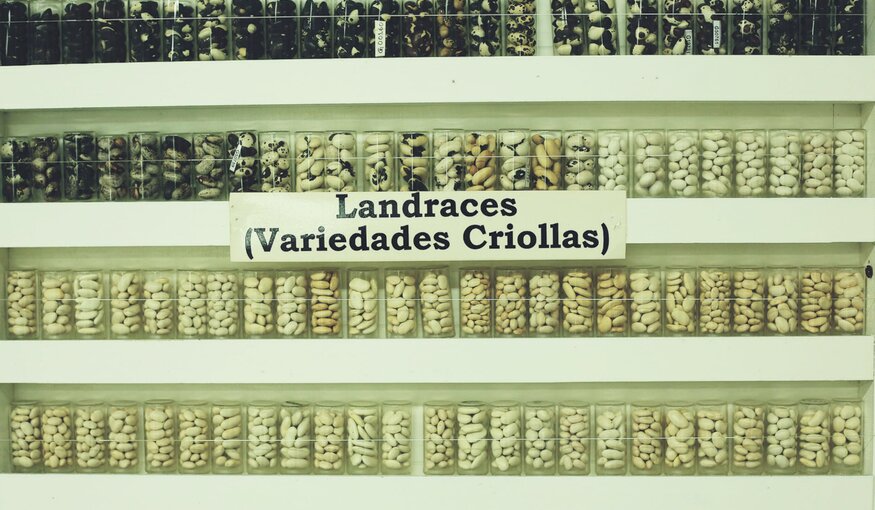

The disappearance of crop diversity, especially over the past 60 years, has led to extensive efforts to collect landraces, as well as their wild relatives, for conservation in genebanks. This is to ensure their survival and to make them available as genetic resources for breeding new crop varieties. These efforts have led to the establishment of hundreds of genebank collections around the world.

However, the degree to which these efforts have been successful in collecting and conserving crop diversity has been difficult to assess. No one knows for sure how much diversity has already been lost. But it is theoretically possible to compare the diversity that is thought to be cultivated currently with that maintained in genebanks.

A recent global analysis took a major step toward doing just this by studying the diversity of landraces within 25 major crops. These crops include the most important cereals, such as wheat, rice and maize, as well as pulses such as lentils and chickpeas, and starchy roots and tubers, such as potatoes and yams. The work of 53 authors from international agricultural research centers as well as academic, nonprofit and government institutions, the study was able to quantify the enormous contribution that generations of scientists all over the world have made to the conservation of crop landraces over the past half-century.

Seeds of Success

Back in the 1960s, scientists from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and from the emerging CGIAR global research partnership sounded the alarm about the erosion of diversity of crop landraces and their wild relatives, and thus embarked on a major collecting drive. Collaborating with national and local partners, their efforts led to the establishment of the international genebanks of CGIAR, as well as building up national, regional and other ex situ collections.

Such efforts continued in subsequent decades, adapting to an increasingly complex political landscape. Fortunately, the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (Plant Treaty) emerged in the new millennium, providing impetus for more international collaboration. In the past decade, an exciting initiative was launched to better conserve crop wild relatives. More than 4,500 samples from 321 wild relative species related to 27 crops were collected and added to genebank collections.

Maps and Models

Collecting in that crop wild relatives project was informed by a conservation gap analysis, which attempted to quantify where these species had already been collected, and to identify conservation gaps, leading to an understanding of global conservation priorities for these wild cousins of landraces.

With the support of the CGIAR Genebank Platform, this gap analysis approach was then extended to the landraces themselves, which are much harder to analyze because they grow not only where the climate and other ‘natural’ factors determine, but also where people decide they should grow. This human element makes it more difficult for computer models to project where domesticated crop diversity might be found.

The two gap analyses had several parallels. Both were led by the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), both studied beans (wild relatives and landraces) as a pilot to develop the methodology, and both published their results in the same journal, Nature Plants. They also share a mission by enabling better indicators for Aichi Target 13 of the Convention on Biological Diversity as well as Target 2.5 of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Farmers’ Favorites

Like crop wild relatives, landraces are known to have high levels of genetic diversity, offering resistance to pests and diseases, tolerance to extreme temperatures and salty soils, as well as different flavor and nutritional profiles. These heirloom varieties have been cultivated by Indigenous or traditional agrarian societies for centuries, helping sustain local agriculture, human nutrition and cultural identity.

Unlike crop wild relatives, however, the conservation gap analysis suggests that landraces have been relatively well collected over the years, with about 3 million samples now maintained in genebanks around the world. The authors of the new study spent three years traveling to the CGIAR collections of crops such as wheat, rice, maize, potatoes, beans and cassava to assess their representativeness.

Around 63 percent of landrace diversity of the crops studied, on average, is likely already conserved in genebanks, which means our chances of achieving the crop diversity targets of SDG 2.5 and Aichi 13 in the foreseeable future might not be too bad. While the official deadline of 2020 has already passed, a post-2020 framework is being negotiated and is expected to extend this date. It seems possible to reach the targets in this next period, at least for the landraces of the 25 crops studied.

Of course, some landraces are more elusive than others. The study found that crops such as breadfruit, bananas and plantains, lentils, common beans, chickpeas, barley, and bread wheat are among the most fully represented in genebanks in terms of landrace diversity, while the largest conservation gaps likely persist for crops such as pearl millet, yams, finger millet, groundnut, potatoes and peas. All of the crops require some further attention somewhere around the world.

Action in the Field

As with the crop wild relatives analysis, the landrace study was not just a scientific exercise, but rather research for action. The results will feed directly into collecting efforts over the coming years. These are currently focused on about 10 countries, hopefully with more to come.

The remaining places for collecting landraces tend to be the most remote and hardest to access, requiring extensive local knowledge. Filling the final gaps won’t be easy.

As my colleague Julie Sardos remarked from her experiences of collecting banana landraces for many years, farmers in the Cook Islands are aware that some landraces of their traditional Fe’i bananas are disappearing due to climate change and social factors. Yet each remaining landrace was being cultivated by only a few people –and many young people barely knew these bananas were even edible.

So where in the world will scientists need to go to find this missing diversity?

Gaps in landrace diversity of the 25 crops may be found in specific parts of South Asia, the Mediterranean and West Asia, Mesoamerica, sub-Saharan Africa, the Andean mountains of South America, and Central to East Asia, according to the study. All over the world, really, but only in particular localities that are mostly remote and hard to find.

A half-century after it began in earnest, the race to collect crop diversity continues. No doubt, if we were to extend the search beyond the 25 crops in question, it would reveal many more conservation gaps, including for fruits and vegetables, for which increased production is certainly needed to address global health challenges. But we haven’t done too badly so far, and that gives hope for the future.

Colin Khoury is a researcher at the Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), and Senior Director of Science and Conservation at the San Diego Botanic Garden

The opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the Crop Trust. The Crop Trust is committed to publishing a diversity of opinions on crop diversity conservation and use.

We'd like to hear from you about this or any of our other articles. Reach out to us with news tips or your thoughts at editor@croptrust.org.

Categories: Genebanks, Climate Change, Nutritional Security