How Genebanks Helped Ahmed Bring Back Cowpea to Somalia

IITA scientist inspects vials of different cowpea varieties. Photo: IITA

10 February 2026

There is no security without food security. In Somalia, a country plagued by decades of civil war, prolonged drought and repeated famine, that link is stark. Nearly a quarter of the population is still underfed and malnourished. When the food system fails like this, everything else could soon follow.

That reality underpins the work of Dr Ahmed O. Warsame, a Somali researcher based at the Crop Science Centre, Department of Plant Science of the University of Cambridge in the UK, where he leads the Legume Crop Resilience and Quality lab. His passion is cowpea, a crop whose decline in Somalia mirrors the country’s recent history.

“One hundred percent, without genebanks, I wouldn’t have been able to get the raw material I need to revive cowpea in Somalia,” Warsame says. “If this diversity had not been conserved, and the genebanks that hold it were not supported by the Crop Trust and other donors, we wouldn’t have anything to bring back.”

A Memory That Lasts

Warsame’s interest in cowpea is deeply personal. He was born in the early 1980s into a pastoral family that moved with their camels. His family were not farmers, because mobility was their way of life, but crops such as sorghum were nevertheless part of daily life, sourced from relatives and nearby villages. Cowpea, however, was a rarity.

In 1993, amid the upheaval that followed the collapse of Somalia’s government, his family passed through a village to meet his older sister, who had fled from Mogadishu. She shared a meal of cowpea mixed with rice, ghee and sugar.

“That meal stayed with me. And changed my life,” he says. “That delicious meal sparked a dream of living with my sister in the village, which my mother soon fulfilled. Later, I moved to Mogadishu with my sister, and that gave me the chance to go to school”.

After school, as he embarked on a career in science, that small event shaped his view of cowpea not as an abstract research subject, but as nourishment, opportunity and hope.

Cowpea pods ready for harvesting. Photo: IITA

A System Under Strain

Somalia’s food security depends largely on three crops: sorghum, maize and cowpea. Cowpea is the most important legume, supplying affordable protein, improving soils by fixing nitrogen and fitting well into intercropping systems. Yet its diversity has been steadily eroding, due to climate change, conflict, and the absence of conservation efforts for over three decades.

Before the civil war, there were some efforts to improve the crop, including introducing new varieties from abroad. In the 1980s, one new cowpea variety performed well agronomically, but failed because consumers disliked its seed color. When conflict erupted in 1991, farmers were displaced, seed systems collapsed and many local cowpea landraces quietly disappeared. Emergency seed distributions filled urgent needs, but often with foreign varieties that were never properly tested under Somali conditions, and often didn't do well.

The consequences are visible today. Surveys show declining yields, repeated crop failures and a persistent mismatch between what farmers grow and what consumers want. Yet, demand for cowpea remains strong, particularly in cities, where red-seeded varieties are essential for dishes such as Ambuulo. In some years, cowpea is even more expensive than imported rice.

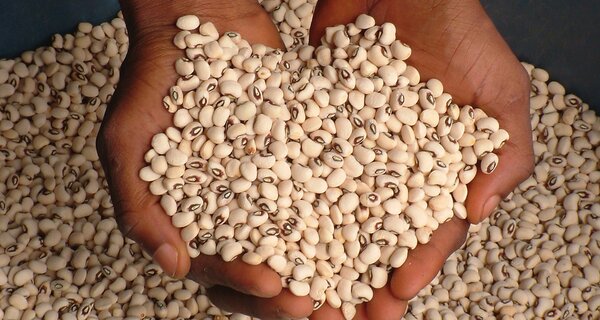

A snapshot of cowpea diversity collected by Warsame’s team across Somalia. Photo: Ahmed O. Warsam

Almost Lost, but not Quite

Warsame’s response has been to rebuild cowpea from its genetic foundations. Somalia is in East Africa, a center of cowpea diversity. If well adapted varieties exist, that is where they will be – or were.

Using information from the global crop diversity database Genesys and decades of research papers, Warsame traced Somali cowpeas held in genebanks worldwide, including at the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) in Nigeria, which holds the world’s largest collection of the crop. The Crop Trust’s Endowment Fund is one of the proud supporters of the IITA genebank.

Abdulkadir Issak, a research assistant, collects data on the assembled cowpea germplasm in the field at Zamzam University near Mogadishu. Photo: Ahmed O. Warsame

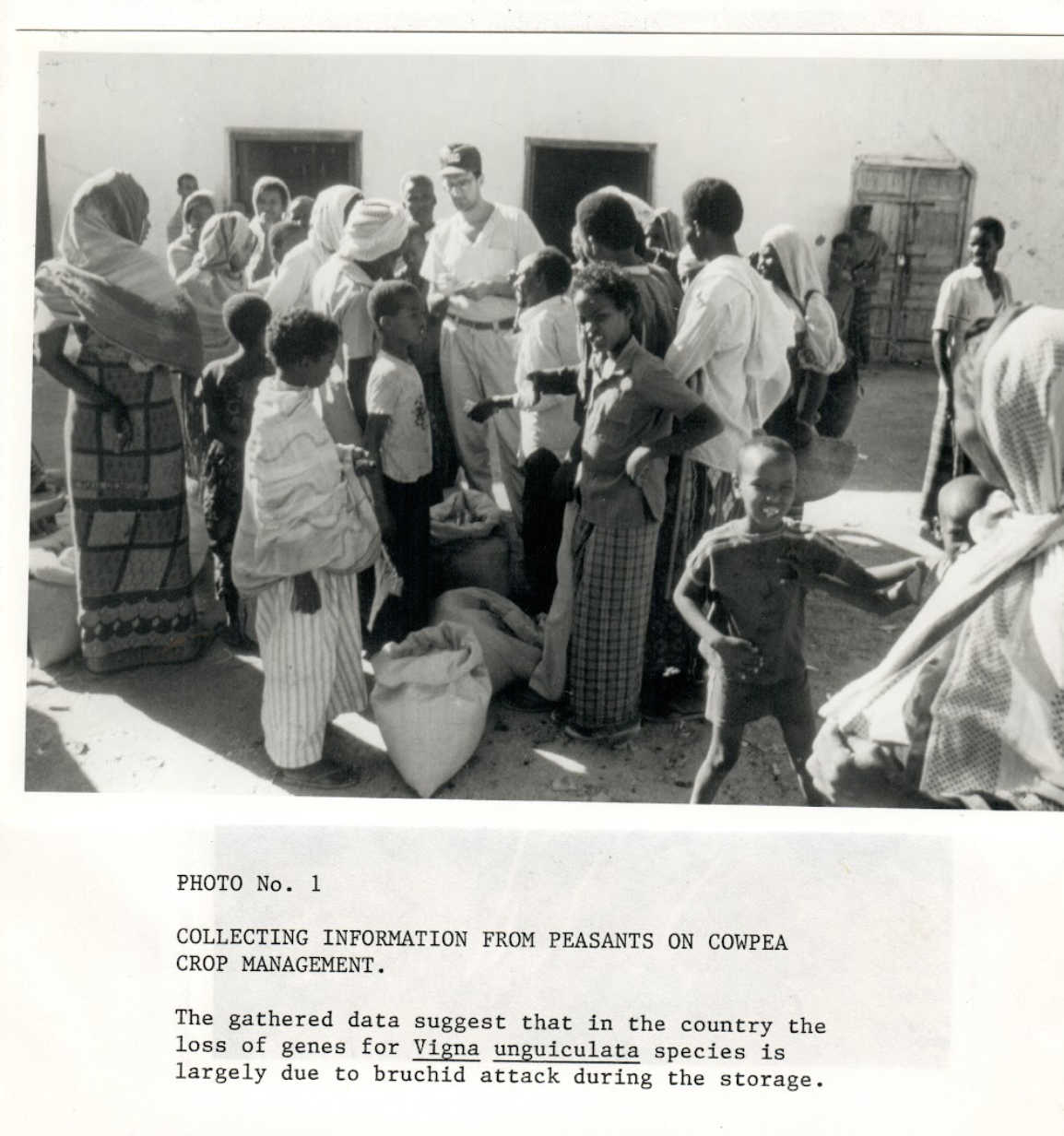

In 1988 and 1989, just before Somalia’s civil war, IITA plant explorer Dr Stefano Padulosi led a months-long collecting mission around the country. “The mission to Somalia was quite challenging but extremely exciting for the landscape, people and culture,” Padulosi recalls. “Cowpea diversity was already eroding due to drought and post-harvest insect damage. Conserving it mattered.”

Dr Padulosi interviews Somali farmers in 1988. Photo from Stefano Padulosi’s personal archives.

That foresight now underpins Warsame’s work. In addition to historic Somali diversity he obtained from IITA, the Australian Grain Genebank (AGG) and the US Department of Agriculture’s genebank, his team also carried out new collections in Somalia in 2025, gathering seeds from cities, villages and farmers’ fields.

From Cold Rooms to Test Plots

A wide variety of Somali cowpeas is now being tested alongside varieties from Niger, Mali and other arid regions at the Zamzam University of Science and Technology, with support from Somali universities and the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation of Somalia.

Farmers are closely involved. Surveys across three regions revealed their priorities: resistance to drought, pests and diseases; early and uniform maturity; fast cooking; and grains that are easier to digest. Seed color preference varies by region, with dark red liked near Mogadishu and lighter shades elsewhere.

Dr Warsame surveys women working at a grain market in the capital of Somalia, Mogadishu. Photo from Warsame’s personal archives.

“Farmers care about how their field looks,” Warsame says. “They literally look at the architecture of the plants, the way the crop stands, spreads and matures, and whether it fits their land and their markets.”

Genebanks to the Rescue

Warsame’s work is possible only because crop diversity was conserved decades ago, far from the fields where it is now needed. Genebanks are useful in emergencies. But they are much more than that. They are a critical part of the long-term infrastructure of agricultural development.

Because that infrastructure was funded and maintained, in places like IITA, Somalia now has the chance to move beyond short-term aid and rebuild its food system from the roots up, literally. Seeds collected before a war, stored thousands of kilometres away, in another country, are the raw material of recovery, and hopefully prosperity.

IITA’s Genebank Manager, Dr Olaniyi Oyatomi shows a sample from IITA’s cowpea collection. Photo: Marta Millere/Crop Trust

“Somalis need to bridge a forty-year gap in crop diversity,” Warsame says. “We cannot do that alone. And we don’t have to.”

Building food security needs patience, continuity and institutions built to withstand crises. Genebanks embody all that. Investing in genebanks is not just saving seeds. It is safeguarding choices for farmers, resilience for food systems and the possibility that, even after decades of tears, a country can perhaps smile again. Ahmed Warsame certainly is, as he remembers that fateful meal with his sister.

Categories: Cowpea, Food Security, Nutritional Security